Part 1: The Selkirk Settlers

Lord Selkirk’s compassion for the Scottish crofters helped seed the Canadian prairies with a population that helped retain the land for Canada. They faced many struggles surviving the early decades and becoming successful farmers. Because of their success the prairies were then settled by waves of immigrant farmers attracted by free land and fueled by the Canadian Government’s support for the railroad.

Sea Floors, Volcanoes & Ice Sheets – Natural History, 125 million BP – 12,000 BP

Surface Landscape – Remnants from the Pleistocene

Profile through southern Manitoba along a line just north of the international boundary showing relief, natural vegetation and surface materials.

The Boundary Trail National Heritage Region possesses an unusually wide range of interesting and unusual landscape features. There are super-flat flood plains; a one hundred meter high linear escarpment; deeply eroded flat-bottom river valleys; v-shaped gorges; rolling hills; large isolated buttes; and densely forested rolling highlands permeated with small sized lakes – to list but a few of the many interesting natural features to be found in the region.

And all of it – the entire current topography of the current BTNHR, was created during the melting of the last continental ice sheet which began to melt away approximately 15,000 years ago. At one point the region was buried under ice sheets 2,100 meters thick.

By 10,000 BP the plateau, now known as Turtle Mountain, was the first area in what is now Manitoba to be ice free and before long the region was supporting evergreen forest and various types of forest wildlife. Only a short distance to the north and east, massive amounts of sediment laden meltwater was accumulating along the ice front, creating deep lakes and at times massive spillways a kilometer or more wide draining these shifting glacial lakes. The largest and best known of these glacial melt-water lakes, Glacial Lake Agassiz, covered much of what is currently Manitoba, North Dakota and Minnesota, the former lake-bed of which is now known as the Red River Valley.

In the areas where the melt-waters did not pond but drained away from the ice face, the material that had been caught up in the ice was simply dropped in place creating a rolling topography of mixed glacial materials, rock, boulders, clays and gravels. In the areas where streams were formed the material they carried were frequently deposited as sand bars, gravel ridges – and similar ‘stratified’ or ‘sorted’ glacial deposits. In areas where lakes, large and small were formed, clay deposits were formed as the smallest of the waterborne glacial materials, settled to bottom in the undisturbed deepest parts of these lakes. The ice sheets did not melt back uniformly. On occasion the ice advanced for some years, and on occasion the rate of ice advance was roughly the same as the rate of melting, In these cases the material carried along within the glacier, accumulated at the ice front creating larger and higher deposits of mixed glacial material. The Cypress Hills, just to the north of the BTHR, were formed in this manner.

Knowing how the various land-forms and topographic features in the BTNHR were formed can make even seemingly minor features of interest and the BTNHR offers some of the finest collection post glacial landscapes on the Canadian prairies. These features include entire districts as well as individual sites.

These include the following:1. erosion feature & stagnant ice moraine (Turtle Mountain); 2. Lake Souris glacial meltwater spillway (Souris and Pembina River valleys); 3. Pembina Hills – Manitoba Escarpement (glacial erosional feature); 4. Glacial Lake Agassiz lakebed – (Red River Valley); 5. Captured Stream – Souris River elbow; 6. Terminal Moraine – Tiger Hills

***

1.3 Turtle Mountain highlands

The Landscape feature known as Turtle Mountain has long been noted and referred to in the diaries and maps of early explorers as a major landmark and important feature on the landscape of the northern Great Plains. It rises from a smooth plain about 1600 feet above seas level to a elevation, at its highest point of about 2400 feet above sea level, or approximately 750 meters above the surrounding plain.

The topography of Turtle Mountain is due in part to erosion and in part to glacial deposition. Approximately two kilometers of sedimentary rock overlays the Precambrian basement beneath Turtle Mountain. This overlay consists of layers of sand, silt and seams of lignite coal. Erosion over millions and millions of years reduced the height of the Mountain before glacial ice covered it.

As the ice thinned and melted with increasingly temperatures, debris that was carried by the glaciers was deposited over Turtle Mountain. These deposits measure about 150 meters in thickness and site atop older deposits and the eroded base. By about 12,800 years ago Turtle Mountain was free of ice. As the glacier melted and the ice front retreated the slumping glacial materials left many shallow lakes and wetlands on the surface of the Mountain and shaped the gracefully rolling hills and dales. Over eons steep sided ravines were cut into the hillsides as rain and runoff waters from the higher, forested elevations to the surrounding plains.

Credible evidence suggests human occupation or use of the Turtle Mountain area that dates back 10,000 years ago, at a time when glacial ice still occupied much of what is now central and northern Manitoba. First known human residents were the mound builders, who left little evidence of their passing other than the mounds themselves. Then the Clovis people who hunted the prairie plains for the mammoth to be followed by nomadic First Nation hunting groups which subsisted off the migrating herds of bison.

Early explorers and fur traders who visited the Turtle Mountain district included La Verendrye during the 1730’s who referred to the mountain as the “Blue Jewel of the Prairie”. During the 1860s the Dakoka moved into the area from the current states of Minnesota and North Dakota to escape conflict with the american cavalry and made their home in Turtle Mountain. The Red River Métis frequently hunted on the plains north of the mountain and wintered in its upland forests from the 1830s to the 1870s. European settlement of the area exploded during the late 1870s and early 1880s.

A forest fire swept through the area in 1898 leaving only the island on Max Lake unscathed, while the rest of the mountain was lest a wasteland of charred scrub. Earle Currie the son of an early area homesteader recalled the event: In 1898 when I was a boy on the farm, the Turtle Mountain forest caught fire and as there was no fire-fighting equipment, it burned for days, the black smoke blocking out the sun. (MHS, Earle M. Currie interview.)

Today the forest and bush land of Turtle Mountain offers a safe refuge for a vibrant ecosystem made up of a variety of plants and animals, birds and insects. As well, Turtle Mountain Provincial Park and the International Peace Gardens provide public access to much of the Turtle Mountain highland areas.

(Sources include: 1. Gerhard Ens, 1982; 2. Norman Wright, 1949, 2. Turtle Mountain Conservation District literature.)

SLIDESHOW: Turtle Mountain – maps and views.

***

Bentonite Deposits and Marine Fossils

Some of these remarkable finds are on display in the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre in Morden, where they form the largest collection of its kind in North America. Among the most fascinating fossils of this collection are the reptile remains, in particular the moasaurs and plesiosaurs.

(Sources: Carr, Karen. C.F.D.C. Pamphlet, 2013. R.M. of Louise History , 1979; BTNHR research files)

CLICK ON THE FOLLOWING LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE BTNHR:

Mammoths, Burial Mounds & Buffalo Jumps – Pre-Contact Indigenous Period, 12,000 BP – 1670 AD

PRE-CONTACT INDIGENOUS PERIOD – 10,000 BP to 1730 AD

Approximately 16,000 years ago, North American temperatures gradually began to rise and the huge glaciers began to melt. Nevertheless it still took about 5000 years before this ice had melted back north sufficiently to uncover southern Manitoba. The Turtle Mountains were the first areas to be freed of this massive ice pack and by 11,000 B.C. the Tiger Hills are believed to have also been ice free. As the ice receded northwards and the ice-front meltwaters drained away, spruce forests soon became established on the newly exposed ground – the northern tree-line following the retreating ice front. Despite the cool and damp conditions, spruce would have been able to grow on the glacial debris as soon as fifty years after the departure of the ice. As the land dried and the climate continued to grow dryer and milder, ash, poplar and birch would have followed. As the forests spread over the region the land became capable of supporting wildlife but the returning wildlife population and diversity was limited as the spruce forest vegetation would not have attracted big game animals nor early human hunters following such game.

However, as the climate gradually became drier still, during a period known as the “Altithermal Period” from about 8,000 to 2,500 B.C., the forests were slowly replaced by prairie grasslands. In Manitoba these grasslands extended considerably farther to the north than seen in recent centuries. Vast areas only recently covered with glacial moraine and out-wash and meltwater lakes now became ideal pastures for a variety of now-extinct animals. Archaeological remains show that these included: ancient horses; camels; four-horned antelope; giant bison, armadillos and ground sloths, as well the impressively large woolly mammoth and mastodon. Mammoth remains have been discovered in fifteen separate locations in Manitoba. A section of mammoth tusk was recovered from a gravel pit near Boissevain and is now in a Brandon Museum. A well preserved mammoth tooth was found in a gravel pit near La Riviere and is now on display in the Pilot Mound Museum. The human population during the pre-contact era has been divided into three principal periods or phases by archaeologists. These are the: Paelo, Meso and Neo-Indian Phases.

Paleo-Indian Phase – 10,000 to 5,000 B.C.

With the change from spruce forests to open grasslands during the “Altithermal” period, ancient bison came in large numbers and the human followed. Referred to by archaeologists as ‘Paleo-Indians’, these stone-age people arrived about 10,000 years ago from the plains to the south and southwest where periodic droughts drove wildlife and human populations northward in search of food and water. The various cultures of early Native people that lived and hunted in the northern Great Plains including what is now southern Manitoba, are identified by archaeologists through the design of the stone points with which they tipped their weapons.

The oldest archaeological culture of the Paleo-Indians, is the Clovis Culture, named for a town in New Mexico where their stone tool artifacts were first discovered. These natives developed distinctive, finely made stone spear points that were sharp enough to penetrate the thick hides of the Ice Age mammoths and bison they hunted. Generally “Clovis Points” are four to five inches long with nearly parallel sides close to the base. Carefully thinned and extremely sharp, near the base the edges are deliberately dulled in order not to cut the lashing used to attach the point to the shaft. Particularly characteristic is the thinning of the base of the point where the split spear shaft was lashed to the point.

Because Manitoba was still largely buried beneath glacial ice during the main period of the Clovis Culture, approximately 12,000 years ago, Clovis artifacts are understandably rare in this province. Only four or five Clovis points have been discovered in Manitoba which are believed to be about 10,000 years old. One of these was picked up on 36-1-8W, eight miles south of Darlingford. This flint point, only a little more than three inches long, is the hard evidence that the earliest known people on the North American continent, the Clovis people, were present in southern Manitoba and explored and hunted in the Turtle Mountains. It is believed that the Clovis people hunted primarily Mammoth and big-horned bison and that their presence in southern Manitoba was fairly short lived, given the rarity of Clovis artifacts.

After the departure of the Clovis people, the mammoth and the big-horned bison, were in turn hunted by the Folsom people who, invented the use of the atlatl to increase the killing power of the spear. This simple invention, consisting of a stick with a notched end into which the butt end of the spear was placed, greatly increased the strength and velocity by which spears could be thrown. There is speculation that the spear thrower was so efficient in hunting mammoths and mastodons that this single innovation contributed to the extinction of the ‘mega’ sized mammals on the North American continent such as mammoths, mastodons, sloth and giant bison. The Folsum points, which were used from approximately 8,000 to 5,000 B.C. have also been found in locations across the BTNHR. When the mammoth and big horned bison were hunted into extinction a species of smaller bison, or buffalo as they are more popularly called, took their place on the grasslands. Spears were the principal weapons of the region’s hunters for the first 5,000 years of human occupation in the BTNHR, bows and arrows being a relatively modern invention in North America.

Meso-Indian Phase – 5,000 B.C to 900 A.D.

As the climate became dryer and warmer and grasslands replaced the forests on the northern Great Plains, the somewhat better-watered parkland areas and highlands, such as Turtle Mountain, provided welcome refuge for wildlife and human populations from the frequently drought stricken southern plains. Weapon points during this period underwent change in both shape and style, and a hunter’s arsenal now included darts and lances as well as spears. Another new innovation that appeared during this period was the use of native-copper, which was used to make everyday tools, weapon points, knives and fish gaffs. The copper originated in the Upper Great Lakes region indicating a trading network and or group migration from that region. Another Meso-Indian period innovation was shell-working. Freshwater clams were collected along major river systems and lake shores and used mostly for body ornament but also as scrapers and small bowls. The clams would also have been a seasonal food item.

As during the earlier Paelo-Indian period, bone-working continued but bone was now also being made into barbed harpoons for fishing. The harpoons and fish bones founds in archaeological digs indicates that fishing was likely commonplace in southern Manitoba with sturgeon bones positively identified.. Bones found at digs at former campsite showed that beaver, deer, canids and rabbits were also being hunted by Meso-Indian groups in south western Manitoba. Only small amounts of duck bones were present indicating little success hunting waterfowl by the Meso-Indian period people. This time pre-dated the use of the bow and arrow.

On the other hand, the distinct abundance of skin-working stone tools found by the Province’s archeologists points to considerable use of leather and hides for clothing and shelter. Another interesting archaeological find stemming from this period were remains of cooking pits, evidenced by fire-cracked roots in filled in pits, pointing to roasting as a mean of fool preparation.

De-hairing and smoking hides.

Neo-Indian Phase – 500 B.C to 1650 A.D.

In terms of found artifacts, the roughly 2,000 yearlong “Neo-Indian” time period offered the richest and most complex finds, indicating a fairly sophisticated and well developed society. There were many new innovations. Among them was pottery making. Remains of large round-bottomed jars have been found in several locations. These vessels would have been used for carrying water and boiling food. Impressions on many of these pots points to fabric making. Dip and gill nets were also being made possibly using leather thongs and perhaps plant fabric, evidenced by found net sinker stones.

Stone and bone working became very sophisticated during this time which now included grinding and polishing of stones. In addition to scrapers, weapon points and net sinkers, grooved hammer stones were commonplace items. Stone wood-working tools were also being made, such as adzes and axes. This allowed for the construction of corrals or ‘pounds’ into which bison would be chased and slaughtered. A site near the forks of the Souris and North Antler rivers is known to have been a long term bison run site. For thousands of years prior to the use of bison pounds as a hunting technique, native groups drove bison herds off cliffs and into gullies where they could be more easily killed, such as at the Claybank site near Clearwater. But the post holes found near North Antler River, gives clear evidence of wood working in the construction and maintenance of this particular bison corral.

As during previous periods, stone-chipping continued to develop with very finely detailed work being done. Significantly, and for the first time, there is clear evidence that stone arrowheads were being fashioned, indicating the appearance of the bow and arrow. This new innovation allowed for the hunting of much more waterfowl, which is evidenced by bones fragments found in former campsites from this period. The use of the bow and arrow and bison corrals allowed for the acquisition of considerable amounts of meat all at one time. This made it possible to support a larger number of people, and the native population very likely grew significantly during this period, as it did after the acquisition of horses during the early post-contact indigenous period.

Bone working during this period also showed development and growth. Digging hoes made from deer shoulder blades indicates that some type of agriculture was being undertaken. Bone awls and needles similarly provides evidence of leather-working. Harpoon heads shows fishing was occurring. Fleshing tools were made from the large bones of hoofed animals. Whistles were being made from bird bones and beaver teeth were used a chisels. Freshwater shells were used as paint dishes, with evidence of ochre found in several examples. Salt-water shells from the Gulf of Mexico were used for making beads and pendants, indicating trading connections involving great distances. In addition to the wild game, fish and freshwater clams, berries and fruit also served as a fairly reliable food source. This overall abundance of food resulted in the development of food storing pits, with several oval-shaped storage pits being found in Manitoba. Many museums in BTNHR contain large and interesting ‘arrow head’ collections, as do many farm families in the region, having discovered items on their fields over the decades. Stone points and other artifacts can be seen at several local museums including in Darlington and Deloraine.

Burial Mounds

In the western ‘upland’ districts of the BTNHR, earthen mounds abound on the landscape in sizes large and small. Most, like the Turtle Mountain plateau itself, most are remnant outcrops of Cretaceous Period shales that withstood the glacial scouring of the last ice age. Some of these hills and mounds in the BTNHR include: Pilot Mound, Star Mound, Calf Mountain, Spence’s Knob and Mount Nebo, among others. On top of many of these natural glacial features, Indigenous people of the Neo-Indian Pre-contact Period often made smaller mounds of soil to create burial places for the deceased.

One of a number of mounds investigated by Manitoba archaeologist Chris Vickers during the late 1940s.

The burial mounds found in the BTNHR are believed to have been built by nomadic bison hunters between 500 AD and 1730 AD during the last thousand or so years of the Pre-Contact period. Some archaeologists such as William Nickerson who excavated several mounds during the early 1900s, suggested they were built by people associated with, or influenced by, the vibrant Siouan culture which was centered in the Mississippi River valley region during this time. Other scholars attribute the burial mounds to the Assiniboine people, who still occupied the region during the early days of the fur trade.

Because of their high visibility on the landscape, the region’s many mounds naturally attracted the attention of explorers, fur traders, travelers and later by arriving settlers. Prominent individuals such as Henry Youle Hind excavated a burial mound near the Souris River in 1857; John Schultz and Rev. George Bruce, prominent Winnipeg figures excavated several mounds during the 1870s and 1880s. Charles Bells, a Woseley Expedition member carried out his own excavations during the later 1880s. These along with other, un-publicized excavations were not professionally conducted or recorded and amounted to little more than grave robbing.

The first ‘bona fide’ anthropological investigation of the BTNHR’s burial mounds was undertaken in 1909 by University of Toronto professor Henry Montgomery. Prominent American anthropologist, William Baker Nickerson was commissioned by the National Museum in Ottawa to investigate Manitoba’s mounds and between 1912 and 1915 he excavated sites at: Manitou; Morden; Darlingford; Pilot Mound; and Melita, as well as sites along the Pembina River and north of the Assiniboine River. The region’s mounds were again inspected by Manitoba archaeologist Chris Vickers during the 1940s and more recently by Manitoba Museum curator, Leigh Syms, and University of Brandon Bev Nicholson. Descriptions of their findings were printed in several publications, much of which can be located online, including on the BTNHR and Manitoba Historical Society websites. The region’s burial mounds, and what remains of their contents, are now protected historic sites under the Manitoba Heritage Resources Act (1987). The Sourisford Linear Mounds site has been declared a national historic site. This is one of many sites in the region where the BTNHR has erected site information kiosks.

Buffalo Jumps

Pre-contact Neo-Indian Period presence in the BHNHR is also evidenced by the discovery of several so-called “buffalo jump” sites, two of which have been investigated by provincial archaeologists. One, known as the Clay Banks Bison Jump, is located north of Clearwater near the confluence of Badger Creek and Pembina River, and the second known as the Brockington Site is located about ten miles south of Melita, near the forks of the Antler and Souris rivers.

Clay Bank Bison Jump Interpretative Sign installed by the BTNHR.

Clay Bank Bison Jump Interpretative Sign installed by the BTNHR.

At Clay Bank archaeologists found the remains of an ancient campsite and a nearby jump and butchering site. The many artifacts found and studied permitted the investigators to get a more clear picture and understanding of the life ways of the people who occupied this site. The projectile points found at this site are known as Sonota points and date from between 250 and 600 AD.

Hunting bison was a very complex and strategic activity. The use of cliffs such as at Clay Banks was only one hunting method. In this scenario, a man, very likely covered in a bison hide, slowly approached a bison herd, pretending to be an injured calf. He counted on the maternal instinct of the female bison to lure the others slowly toward the cliff. Piles of rocks and brush would have been lined up to direct the herd to the exact desired location. At the right moment, women and older children would jump up from behind the stone piles, yelling and waving blankets. The startled animals would stampede over the cliff, at the bottom of which a corral compound had been built to contain the less injured animals until they could be killed. The job of butchering the carcasses occurred on site, with the meat

Brockington Archaeological Site is situated on the east bank of the Souris River near its confluence with Antler River near the US border south of Melita. This archaeological site is significant for having been occupied by three separate pre-contact cultures over a 1,200 year period. The bison kill and butchering site component of it stems from around 800 AD. It is quite unusual as the Indigenous people who built it installed a series of vertical posts at the bottom of the Souris river Valley, to build their pound, rather than simply piling stones and brush. Bison would be herded down the steep valley side to run tripping and tumbling into the structure. Archaeologists suggest that this was likely a more efficient method of killing bison than driving herds over a high cliff, as it would have resulted in a minimum of bone breakage. A very large number of small side-notched arrows were found at the site, ranging from 10 to 45 pounds of material per square meter. It is also evident that, after its use, the Brockington pound was dismantled and re-erected – likely, many times over. Most of the post holes discovered had been filled in with vertically placed bison bones and small stones, allowing them to be easily uncovered for pound construction the next season or next visit to the area. The existence of former post holes also indicates that stone blades and axes were being used for “wood-working” purposes. Although not the only site where bison run associated post holes have been discovered, the Brockington Jump Site is one of the first and certainly the best documented cases of such a rare occurrence on the prairies.

***

Sources consulted – Pre-Contact Indigenous

- Abel, Kerry M. “Morton – Boissevain Planning District Heritage Report, Prepared for the Historic Resources Branch, unpublished manuscript. November 1984;

- Ens, Gerhard. Killarney Area Planning District Heritage: Report, Prepared for the Historic Resources Branch, unpublished manuscript, April, 1982.

- Moncur, William W. Beckoning Hills – Pioneer Settlement Turtle Mountain Souris-Basin Areas. Compiled by special committee in conjunction with Boissevain’s 75th Jubilee, 1956.

- Nicholson, Karen. A Review of the Heritage Resources of the DEL-WIN Planning District, Prepared for the Historic Resources Branch, unpublished manuscript.

- Pettipas, L. and A.P. Buchner. “Paleo-Indian Prehistory of the Glacial Lake Agassiz Region” in Manitoba, in “Glacial Lake Agassiz”, ed. by J. Teller, Geological Association of Canada Special Paper 26. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, 2004.

- Turtle Mountain – Souris Plains Heritage Association, Geocaching site cards, 2005.

- Vickers, C., 1949, Projects of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba Archaeological Report 1949. Winnipeg.

- Historic Resources Branch, 1994, First Farmers in the Red River Valley. Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Citizenship. Winnipeg.

Explorers, Traders & Map Makers – the Fur Trade Period, 1670-1870

The Fur Trade in BTNHR and Southern Manitoba

The Boundary Trail National Heritage Region (BTNHR) is exceptionally rich in terms of fur trade era sites and events. While its largely prairie/parkland natural landscape prevented it producing large numbers of furs and pelts, the Region was nevertheless well known to fur traders and explorers throughout the entire 200 year interior fur trade period. It was the location of some of the earliest fur trading posts and most significant events, and its rivers and forests were explored by some of the best-known fur traders and map makers. It was the first Region in the west to be a source of pemmican, the main food for the canoe and ox-cart freighting brigades. And it was the birthplace of the famous Red River Cart and home to some of the earliest Métis settlements in western Canada. Following is a brief history of the interior fur trade with specific reference to the Red River region and the BTNHR.

French vs English

The fabled North West Passage was the prize that the earliest explorers such as Henry Hudson in 1610 and Thomas Button in 1612 were searching, as it was for many who followed them. What they found instead was the bleak, barren, shores of Hudson Bay which did not offer a way to China but, however, gave early promise of furs – much valued in Europe at the time. It remained for two Frenchmen, Radisson and Groseilliers, who in 1681, by land, traveled to and explored the region south of Hudson and James bays returning to Montreal with many valuable furs to confirm the Region’s great abundance of furs. Because of a quarrel with the authorities in New France, the two explorers transferred their services to England. In 1668, Groseilliers sailed into James Bay on the ‘Nonsuch’ and returned to England the next year with a rich cargo of furs. As a result of this success, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) or ”the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay” was formed in 1670 by Royal Charter granted by Charles II giving the Company exclusive trading rights to the Hudson Bay watershed. It was destined to become the oldest Company in the world.

Over the next few years, the HBC constructed and staffed three trading posts on James Bay: Moose Fort; Fort Charles, and Fort Albany. Over the next few decades, as these posts attracted more and more Indigenous traders, the HBC established additional ‘tidewater’ posts on the shores of Hudson Bay at the mouths of the Severn, Nelson, and Churchill rivers. York Factory, at the mouth of the Nelson River, would later become a major distribution point and post for the HBC.

While the English fur traders were coming to present day Manitoba by sea, the French, also in search of the ‘western sea’, were coming by land. Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye, the first European to explore what is now southern Manitoba, established a series of forts in the Red River – Lake Winnipeg region during the 1730s. These included Fort Maurepas at the mouth of the Red River; Fort Rouge at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers; Fort La Reine on the Assiniboine River near Portage la Prairie; Fort Dauphin in 1739 near Lake Winnipegosis, and Fort Bourbon in 1741 on Cedar Lake near the mouth of the Saskatchewan River. These trading posts they began to intercept much of the Indigenous fur traffic headed to the HBC posts on shores of Hudson’s Bay.

Left: In 1742 La Vérendrye’s two son’s reached the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in their search for the western sea. During their explorations the La Vérendrye’s traversed the current BTNHR region several times and camped on the northern slopes of Turtle Mountain.

La Vérendrye Travels and Forts. In 1738, Pierre La Vérendrye and his two sons visited the Mandans on the Missouri River. Departing from Fort La Reine, they travelled by way of Turtle Mountain and the Souris River Valley. During his trip to the Mandans in 1738, La Verendrye followed an established Native trail, which passed over the Pembina Hills and on to the Turtle Mountain. From his journal description, it appears that his party camped overnight at Calf Mountain. In 1742, his sons, Pierre and Francois, travelled the same route on another visit to the Mandans. (Batchscher,1979: 63)

End of the French Fur Trade

The French-administered fur trade ended in 1760 when, following the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, New France was ceded to Britain. Very quickly, however, the new English business elite taking up residence in Quebec and Montreal set up their own operations in pursuit of the rich fur trade the French had lost. Many of posts and employees were much the same as under the French, only with different bosses. These independent fur traders initially used French Canadian ‘coureur des bois’ to paddle their canoes from Montreal to the western plains, trade with the resident Indigenous groups for their furs, and bring those furs to Montreal. The fierce competition amongst themselves and the enormously expensive distances involved led to a union of most of the investors into the North West Company (NWC) in 1784. The XY Fur Trade Company (XYC) was also formed at this time and, for a time, successfully competed with its larger rivals. There were also a number of short-lived ‘Canadian independent’ traders and American Fur Company posts constructed in what is now southern Manitoba in the years immediately following the fall of New France.

After the formation of the NW and XY trading companies, competition with the HBC increased significantly, with all three companies building new trading posts in attempt to get the Natives’ furs before the others could. Between 1790 and 1816, about 15 different trading posts were established in the Brandon-Swan River district alone, along with a similar number being built in the lower Red and Assiniboine rivers district. Most of the heavy manual labour in the fur trade, especially in the NWC was undertaken by mixed-blood French-Catholic Métis workers, with English-Protestant “country born’ workers supplying the labour for HBC operations.

This early fur trade period was a time of intense competition especially between the NW C and the HBC. During this period, all the major companies frequently moved the locations of their posts, all of which were located along the Region’s waterways, serving as the main transportation routes. Large ‘freighter canoes’ and ‘bateaux’ (flat bottomed rafts) were the main water craft at the time. Eventually, longer-lived major posts were established at strategic locations along the waterways. Employees stationed at these ‘regional’ posts were often sent out to establish small sub-posts or ‘wintering houses’ at one or two days travel distant from the main post, to intercept Indigenous hunters and trappers before they were able to journey to rival posts in the Region. These wintering houses were often abandoned after only two or three years especially if they did not take in sufficient amounts of furs, pelts or pemmican to make the venture profitable.

There were two locations in the current BTNHR that supported such long-lived ‘regional’ posts, at the forks of the Red and Pembina rivers and the area of the forks of the Assiniboine and Souris rivers. As well, the company employees at these posts were often sent out to build smaller wintering posts in the surrounding hinterland. Thus, the BTNHR possesses a long and colourful fur trade history past with major posts and temporary wintering houses having been established at various locations in and near the Region.

Souris River Mouth Posts

One of the first European fur traders to explore the Turtle Mountain – Souris Plains region after the fall of New France was Alexander Henry, a prominent Hudson’s Bay Company trader and explorer who passed through the region in 1776 while on a trading mission to the Mandan villages. He reported that the resident Assiniboine were now in possession of large numbers of horses and, as La Verendrye reported three decades earlier, they still seemed quite indifferent to the white man’s trade goods, having ‘all they needed in the buffalo.” (KN:3)

In 1785, the NWC established Pine Fort on the Assiniboine River a short distance downstream of the mouth of the Souris River to trade furs and, more importantly, to obtain corn, bean, and squash from the Mandan and pemmican from the Assiniboine Indians. These provisions were needed to feed the voyageurs on their long canoe trips from the Prairies to Montreal. The HBC quickly followed suit and erected Brandon House on the Assiniboine River just up steam from mouth of the Souris River.

In 1793, the newly established XYC. led by Sir Alexander MacKenzie instructed its agent, Peter Grant, to build a provisioning post of its own near the mouth of the Souris in support of its growing network of trading posts. This prompted the NWC to abandon Pine Fort and erect a new post ‘Assiniboine House’ that they built in near to both HBC Brandon House Peter Grant’s XY posts. The three rival posts remained relatively profitable though few furs were taken in; mostly buffalo and wolf pelts as well as pemmican were taken in. The three posts operated in near proximity to each other for over a decade without incident. The staff were on friendly terms and socialized frequently.

In 1805, the XYC merged with the NWC, and both XYC ‘Fort Souris’ and NWC ‘Assiniboine House’ were torn down and replaced by a nearby new larger post which was named NWC ‘Fort Riviére la Souris’.

Souris River & Turtle Mountain Out-posts

During the late 1790s and early 1800s, during the peak of fur trade rivalries, short lived ‘wintering outposts’ were commonly built to intercept Indians travelling to the major posts to trade. In the autumn of 1795, the Chief Factor of NWC ‘Assiniboine House’ sent men and supplies up the Souris River with instructions to establish a wintering house. The group erected a site on the left bank of the Souris River just south of present day Deloraine. NWC ‘Ash house’ operated for only a single season. A possible reason for its brief use was noted by David Thompson in December 1797, who, while travelling up the Souris River stopped briefly at the recently abandoned post, noting in his journal that ‘…it had to be given up from it’s being too close to the incursions of the Sioux Indians.”

As well, in 1797, the Missouri Fur Company issued a declaration forbidding British subjects, such as David Thompson, from trading in the Missouri River drainage basin. Thereafter, trading south of the Assiniboine River slowly shifted from trading with the Missouri River Mandan to trading with the Turtle Mountain Assiniboine. The Assiniboine increasingly become a major supplier of pemmican for the various fur trade transport brigades and the Assiniboine River provision posts remained critical elements in the profitability of the various fur trade companies.

In 1801, prairie fires swept across the Souris plains affecting trade and prompting the HBC to establish a sub-post on the northern slopes of Turtle Mountain “so “Indians from the south would not have to cross the burned out plain to reach Brandon house.” (KA:18) The next season, the NWC and XYC both constructed wintering posts ‘on the edge of Turtle Mountain’. However, trade was further disrupted by growing tribal conflicts, with the Assiniboine fleeing the Turtle Mountain due to the arrival of Gros Ventre and war parties of Sioux having been sighted in the region. As a result, trade for furs and provisions was very poor at Turtle Mountain that winter and, in the spring, all traders retreated to their respective establishments around the mouth of the Souris.

The situation soon improved, because, in 1806, Alexander Henry the Younger, on a journey to the Mandans, reported that the Assiniboine were back in the Pembina Hills – Souris plains region and still lived according to a pure buffalo economy. Henry Jr. also noted in his journal during that trip that HBC Lena House was once again functioning as a winter post. (KN:3 &:19)

NWC ‘Fort Riviére la Souris’ remained the Company’s main post on the Assiniboine until the amalgamation of the NWC and HBC in 1821 under the HBC banner. Many trading posts immediately became redundant and were closed soon after and abandoned, including HBC Brandon house II and its various outposts. A third HBC Brandon House was constructed in 1828 but operated for only six seasons before the Souris mouth area was permanently abandoned by the HBC, who chose to develop the more strategically located Fort Ellice, near the mouth of the Qu’appelle River, as the Company’s sole post on the Assiniboine River. (Smyth, 1968:131.)

Pembina Mouth Trading Posts

The mouth of the Pembina River was a strategic and very well-known site. A long series of posts and forts were constructed in the area, especially during the early fur-trade era. The earliest known trading post at this site was a ‘Canadian Independent’ post built in 1793 known as ‘Grant’s House’. In 1796, Charles Baptiste Chaboillé built ‘Rat River House’, a wintering post at the mouth of the Rat River, for the NWC – its first post on the Red River. However, after a single season, the site was abandoned and NWC “Fort Pambian” was erected at the mouth of the Pembina River. Four years later, in 1801, Alexander Henry (the younger), the new Superintendent for the Lower Red River Region, arrived and replaced that post with a nearby larger one. Within a couple of years of the construction of NWC Fort Pambian, opposition posts operated by the HBC and XYC were erected in the immediate vicinity. Because of the threat of Sioux attacks, all of these posts were fairly substantial structures with sturdy blockades, ramparts and guard towers.

As with the Souris River mouth posts, in order to gain more control of the furs being traded, each of the companies set up smaller outposts at several strategic nearby sites. In most cases the posts were not actually forts, but rather one or two small, quickly constructed log cabins occupied for only one or two winter seasons. In some cases, however, such as with the NWC Red Lake outpost, the furs taken in warranted operating the outpost for several years, necessitating larger buildings and the protection of a timber palisade.

The Hair Hills Out-Posts

In 1800, Alexander Henry (the younger), decided to set up a Fort Pembina sub-post in the Hair Hills (Pembina Hills). According to his journal on September 4, 1800, he arranged for a guide named Nanaundeyea and three other men to journey into the hills and build a wintering house there. Henry’s guide, Nanaundeyea, is said to have responded that these hills were within the raiding range of the Sioux and suggested that it would be wiser to wait until after the beginning of October before entering the area when the danger of attack by a Sioux war-party would be negligible. In accepting that bit of advice, Alexander Henry forestalled the departure of the work party until October 1st. Two weeks later, Henry himself journeyed to the site of the Hair Hills outpost to inspect their work and explore the local district.

Between 1800 and 1805, at least five separate NW C wintering houses were established in the Pembina Hills area, with locations being moved each winter. After the second winter, in October 1802, Henry reported in his journal that a party of XYC men had departed their post at Pembina bound for the Hair Hills to build a competing post near his own “Langlois’ House”. Direct competition in the Hair Hills area did not seem to affect Langlois’ trading success since, that winter, he acquired almost as many furs as Henry did at Fort Pembina and much more pemmican. The records from these sub-posts indicate that, for a time at least, the region was rich in furs and a considerable amount of trading took place. (Smyth 1968:117)

Scratching River Out-Posts

In September 1801, the XYC built another sub-post downstream the Red River near the mouth of the Scratching (Morris) River. Not to be outdone, Alexander Henry (the younger) instructed his interpreter, J.B. Desmarais, and five other men to take sufficient supplies and trade goods from the NWC post at Pembina and build a competing outpost at the Scratching River” or “Rivière aux Gratias”, as it was known at the time. The NWC’s Scratching River post proved to be a commercial failure, taking in only 130 beaver skins, seven bags of pemmican and 3.5 packs of furs during the winter of 1801-02. Both it and the XYC post were abandoned after one season.

A New Sort of Cart

Following the relative failure of the Scratching wintering house, Alexander Henry decided to try the Hair Hills district again. In late September 1802, ‘Hair Hills III’ was built at a trail ford across Dead Horse Creek. The site was known as “Pinancewaywining”, and was located a short distance south of present day Morden. The sub-post at Pinancewaywining and another at Red Lake were significant in that they could only be reached overland. All supplies and property had to be brought in using horses. To this end, Henry mentions the use of a “new sort of cart”. This cart “…facilitates transportation, hauling home meat, etc. They are about four feet high and perfectly straight; the spokes are perpendicular, without the least bending outward, and only four to each wheel. These carts carry about five pieces [450-500 lb.] and are drawn by one horse.” (Coues 1897: 205.) Historians have noted this as the first written reference to the now famous ‘Red River Cart’. The carts used to supply the post at Henry’s Pinancewaywining post are now generally regarded as the prototype model for the Red River Cart, though they are quite clearly not the same vehicle: as among other things the wheels of this cart were not “dished”, and the spokes were far fewer than on the later style Red River Cart. These improvements would be evolve over the years as the cart became more commonly used.

The NWC and the XYC merged on November 4, 1804. News of this merger would have arrived in the west with the arrival of the 1805 spring canoe brigades. Henry responded to the news by closing down half the number of posts he formerly maintained. The former XYC posts along the Red and Assiniboine rivers were also closed and absorbed into the NWC operations. Without local XYC competition, Henry realized there was less need to go out and actively pursue his clientele. They had to go to him once again. The NWC posts still outnumbered HBC posts by a significant number at the time so NWC business improved considerably after the merger. Nevertheless, as a result of the merger, sub-posts like those in the Hair Hills, Red Lake and elsewhere along the Red River and throughout the west soon disappeared, by-products of a passing phase in the fur trade.

Arrival of the Selkirk Settlers

After the 1805 merger, the new NWC continued their often-friendly relations with their HBC rivals – until the establishment of the HBC-supported the Red River Colony in 1812. In 1810, the Earl of Selkirk bought a controlling interest in the HBC and used his power to obtain a large grant of land, including all of present day southern Manitoba and parts of Saskatchewan, North Dakota, and Minnesota. He then put into effect his plan to settle displaced farmers, “crofters,” from the Scottish Highlands, at HBC Fort Garry. His plan and the settlers were opposed by the NWC and the Métis, both of whom saw their way of life being threatened. When an additional 100 settlers arrived in 1813, they became very agitated and prepared for trouble.

The HBC Governor, Miles Macdonell, fueled that trouble in 1814, when he issued a proclamation forbidding anyone but the HBC to export pemmican from the Red River region for one year. For decades, pemmican had been the staple food supply of the fur trade and even temporary enforcement of this proclamation would mean financial ruin for the NWC and private traders. So trading in pemmican continued and before long the so-called ‘Pemmican War’ erupted. The HBC raided some private and NWC posts and seized pemmican supplies. In 1815, NWC employees, or ‘Nor’ Westers’ as they were know, attacked and burned the Red River Settlers’ post, Fort Douglas, along with their windmill, stables and barns – the settlers fleeing in disarray. The new colony governor, Robert Semple, on his way to the settlement with 100 new settlers, met the refugees, brought them back and re-established the settlement.

Hostilities only increased the next summer. On June 1, 1816, armed Nor’Westers led by Cuthbert Grant looted and burned Brandon House. On June 19, Grant and his men were intercepted and confronted by Governor Semple and about two dozen armed settlers when they attempted to transport pemmican past the settlement to a NWC post on the Winnipeg River. During a heated verbal exchange, someone fired a shot and a deadly firefight ensued. After the battle, Governor Semple and 20 of the male settlers lay dead, along with a single Nor-Wester, in an event often referred to as the ‘Massacre of Seven Oaks’. The surviving settlers were sent to Lake Winnipeg where they regrouped and camped. Upon hearing of the killings at Red River, in the fall of 1816, Lord Selkirk recruited a private army in Montreal and set out for Red River, capturing the NWC headquarters at Fort William along the way. In the spring he recaptured Fort Douglas, temporarily immobilized the Nor’Westers, and re-established his settlers at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers.

Plan of the Red River Colony circa 1820. Also noted is the “Route of Grant’s horseman” preceding the Battle of Seven Oaks in the summer of 1816.

1821 HBC / NW Company Merger

The competition between the HBC and the NWC had been mutually ruinous and, in 1821, they amalgamated, under the HBC banner. With an end to the competition the new HBC reorganized its vast network of posts and many employees were let go. Especially affected were the Métis and First Nations freighters and food suppliers. While large numbers were still employed, many lost their livelihoods. Some of the Anglo-Scottish employees returned home, others retired to the Red River Colony. Métis settlements were established at St. Vital and St. Norbert on the Red River and St. Francois Xavier on the Assiniboine River. There was also a substantial population of Métis at Pembina and nearby St. Joseph (now Whallaha). In 1822, one year after the HBC and the NWC merger, the American Fur Trade Company began trading in Minnesota developing posts at Red Lake, Sandy Lake, the Minnesota River, Rainy Lake, and Lake of the Woods. American presence and territorial authority increased rapidly thereafter. In 1849, Pembina and, by extension, the Pembina Métis become part of Minnesota Territory prompting many to move north of the international border.

The population at Red River at this time was less than 2,000, most of whom were Métis and Country Born, but also included retired British soldiers and officers; retired or unemployed former HBC and NWC employees, various small groups of Indians, and several hundred Selkirk Settlers. The whites farmed along the Red, but most of the Metis and Natives lived by the twice-annual buffalo hunt which, for years, produced the colony’s only cash crop. The new HBC still required pemmican and furs as well as workers, especially York-boatmen on the northern waterways and ox cart drivers on the growing network of overland trails. Some Métis became illegal independent traders. Due to its virtual monopoly over the fur trade, the HBC was profitable for its shareholders for decades to follow even though demand for furs in Europe was beginning to slow.

The Decline of the Fur Trade in the Red River Region

After the HBC absorbed the NWC in 1821, the new HBC obtained, from the British monarchy, a license for 21 years, granting the amalgamated company a monopoly on trade for the entire British North West Territories. In 1838, the HBC licence was renewed, for an additional 21 years. However, on the expiry of this in 1859, the license was not renewed and trade in the British North West became open to all.

British and Canadian political interest in the territories steadily grew as the fur trade began to decline and American presence on the Great Plains increased. Scientific expeditions were sent out by both the British and Canadian governments (Palliser and Hind Expeditions, 1857-60), to assess the resource and agricultural potential the North West.

New HBC Freight Routes & Modes

In 1852, the westward expanding railway network in the US reached the banks of the Mississippi River and, within a few short years, steamboat and stagecoach connections reached as far north as St. Paul, Minnesota. With these developments, the HBC soon determined that it would be cheaper to transport furs packets and trade goods to and from its main distribution headquarters at Fort Garry to England, south though the US rather than using the original and arduous Lake Winnipeg/Nelson River/Hudson’s Bay route. In 1857, the HBC arranged with the US Treasury to allow a shipment of 40 tons of HBC goods from England through the US, via St. Paul, as sealed, bonded and duty free goods. The packets would be transported by ship from England to New York and from there by railway to steamboat connections at Salema and La Crosse, Minnesota on the banks of the Mississippi River. They would continue on by riverboat to St. Paul, with the last 500 mile leg to Fort Garry completed by ox cart brigade owned and manned by Métis freighters under contract to the HBC. The experiment proved successful and before long the amount of goods being shipped by this route increased tenfold.

In the spring of 1859, the first steamboat on the Red River, the ‘Anson Northup’ was built on the east bank of the Red River near its confluence with the Sheyenne River. In June, the steamboat made a triumphant trip to HBC Fort Garry at The Forks. The Anson Northup was soon acquired by the HBC and, as the rechristened ‘Pioneer’, began to take over some of the transport duties of the ox cart brigades. The ox cart brigades nevertheless continued to be a major component of HBC freighting network for many years. In 1862, the HBC replaced the “Pioneer” with a 137 foot, 133 ton steamboat, the ‘International’. As owner of the only steamboat on the Red, for the next decade, the HBC enjoyed a monopoly on the freight and passenger business on the Red River.

The HBC was not without competition in the taking in of furs and the selling of merchandise during this period. Independent Métis traders were also travelling to St. Paul to sell furs and purchase goods to be sold or traded in settlements and camps across the Prairies, as well as for personal consumption. Additionally, a few American owned posts were established just south of the border, including St. Joseph (now Walhalla, North Dakota) and Pembina, North Dakota, which attracted clients from north of the border. The border at this time was still open and unsecured.

Although the amount of fur and pemmican being taken in had dropped substantially during the 1860s due to the region being hunted out, the HBC maintained some of its Red River region posts. In 1850, when the location of the boundary was determined to be two miles north of Pembina River mouth, the HBC was obliged to move its post to the north side of the border which was renamed ‘North For Pembina’. During this later fur trade period, Upper Fort Garry became the HBC’s main interior supply and distribution centre. York boats still transported goods on the northern waterways, but ox cart brigades increasingly took over the job of freighting for the HBC in the prairie and parkland regions. Virtually all of the freighters employed by the HBC were of Métis or Indigenous background. As pemmican and other types of ‘bush meat’ were still needed to feed the men of the freight brigades, who had no time for hunting for food, the Métis twice annual bison hunts continued to be an important source of food for the HBC. However, by the early 1860s, the bison herds indigenous to the Red River region were disappearing and hunters had to travel further south and west to find the large herds. Most of the activity in the fur trade at this time was shifting to British Columbia and the Athabasca region. Fort Edmonton was the main distribution point for these northern posts. It was supplied from Fort Garry by annual ox cart brigade using the Saskatchewan Trail. Fort Ellice (near St. Lazare, Manitoba and Fort Carlton, near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan) became major stopping points along the Saskatchewan Trail.

HBC Rupertsland Sold to Britain

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 delayed further US expansion in the Dakotas and also delayed British action on acquiring the HBC’s ‘Rupertsland’ territories. However, after the war ended in 1865 growing “manifest destiny” and ‘Irish Fenian’ movements in the US, the British Government moved to take over administration from the HBC and to transfer authority over the west to the newly established Canadian Dominion Government.

The fur trade was dying anyway so HBC did not protest but sought ways to profit by the settlement to come. In 1969, the Company’s territorial possessions were officially surrendered to the British government for a consideration of 300,000 pounds (approximately $1,500,000) and 1/20 of the lands in the fertile belt, which amounted to almost 3,000,000 acres of potential farmland.

In addition, the HBC was also able to retain sizable land reserves around existing posts. In Manitoba these included around: Upper Fort Garry, Lower Fort Garry; Fort Ellice; Riding Mountain House; and North Fort Pembina. The HBC reserve at North Fort Pembina was surveyed into town lots and registered in the Manitoba Land Titles as the town site of ‘West Lynne’. The HBC also established a number of stores in selected communities across the Prairies, including in Manitou in the BTNHR. Later, a chain of HBC department stores were established in the principal cities of the West and thus, for many decades after the end of the fur trade, the Hudson Bay Company continued to be a major presence in the west with stores in many towns and cities. The large department stores, such as Winnipeg’s landmark structure, were a far cry from the small isolated woodland posts where basics such as tobacco and tea, blankets, knives and firearms were bartered for pelts and pemmican.

Red River Resistance and the Dominion Survey

As part of its plans to facilitate the acquisition and settlement of the HBC’s western holdings, the new Canadian Dominion Government proposed the construction of a railway linking eastern Canada with the colony of British Columbia on the west coast. It also proposed the surveying of the entire west into uniform ‘‘townships and sections’ to quickly and efficiently facilitate the settlement and agricultural development of the west. However, neither the HBC nor the Dominion Government thought to officially inform the people already living in the west of the land transfer and forthcoming pre-settlement Dominion Survey. When survey crews suddenly began staking survey lines near the Red River settlement during the summer of 1869, the resident population and, in particular, the Métis protested and then resisted by forcibly stopping the survey crews. The Red River Resistance or “Rebellion” ensured. The crises ended a year later, with the arrival of the soldiers of the “Red River Expeditionary Force”, also known as the ‘Wolseley Expedition’, and the news of Red River Settlement joining Canadian Confederation as the new Province of Manitoba. By the early 1870s, agriculture and forestry had overtaken the fur trade as the primary resource based industry of the economy in both the BTNHR and southern Manitoba in general.

By the early decades of the twentieth century all traces of the early fur trade posts, even the larger forts, had disappeared from the landscape with only underground archeological remains left to testify to the wealth of history and human experience that occurred at these sites and in the BTNHR region as a whole during the two century long fur trade period.

***

For additional information and stories about the fur trade in and around the BTNHR, click on the links below:

- La Vérendrye and his Sons – In Search of the Western Sea, 1730s

- The Wanderings and Sufferings of John Pritchard, 1805

- The Scalping of Marguerite Trottier, 1809

- A Rather Colourful Caravan, 1802 – by Alexander Henry

- A Four Year Residence at the Red River Colony, 1820-24 – Rev. John West

- Peter Rindisbacher – Red River Colonist and noted Artist. 1821-26.

- Lord Selkirk and the Red River Settlement, 1812-1870

- Paul Kane – Artist in the British North West, 1845-48.

Sources consulted for Fur Trade Period overview above:

Christopher 1962. Henriette Christopher: “Pictorial Map of Historic Pembina.” 1962;

Coues 1965. Elliott Coues: “New Light of the Early History of the Great Northwest, Minneapolis, MN, 1965. p 205;

HRB 2001, Ash House. Province of Manitoba, Historic Resources Branch pamphlet, “Ash House”, 2001;

Jenkinson 2003. Clay Jenkinson: “A Vast and Open Plain – the Lewis and Clark Expedition in North Dakota”, 1804-1806. State Historical Society of North Dakota. 2003;

Kavanagh 1960. Martin Kavanagh: “The Assiniboine Basin”, Givesham Press, Surrey, England, 1960. p.32;

Kavanagh 1967. Kavanagh, Martin. “La Verendrye: His Life & Times”, Fletcher & Sons Ltd. Norwich England, 1967;

Ledohowski 1981. Edward M. Ledohowski: “An Overview of the Heritage Resources of the Neepawa and Area Planning District”, Historic Resources Branch, Department of Cultural Affairs and Historical Resources. 1981;

Nicholson 2001. Karen Nicholson: “The Pembina Mėtis”, Historic Resources Branch pamphlet, February, 2001;

NWF 1920 Jan 20. Nor’-West Farmer, January 20, 1920, ”The Hudson’s Bay Company, Past and Present”;

NWF 1920 Mar 10. Nor’-West Farmer, March 10, 1920. p. 404. “A Bit of Canadian History”;

Payne 1968. Michael Payne: “Fort Pinancewaywining” , Historic Resources Branch pamphlet, November, 1980;

Symth 1968. Terry Symth: “Thematic Study of the Fur Trade in the Canadian West, 1670-1870”’. HSMB Agenda Paper #1968-29. 1968;

The National Atlas of Canada, page 79, “Posts of the Canadian Fur Trade”;

Beckoning Hills Revisited.

Mounties, Scientists & Surveyors – Expeditions, 1857-1874

During the nineteen century at least five major expeditions traversed either the length or major portions of the current Boundary Trail National Heritage Region. Few other regions in western Canada hosted such a variety of scientific, military, survey and police based expeditions, in some cases involving hundreds of men and wagons crossing many hundreds of miles of open prairie. Their eventful experiences while travelling through the region make up some of the most interesting of all the amazing true stories to be found in the BTNHR. These expeditions include:

1. The British North American Exploring Expeditions, 1857-59.

2. The Dominion Land Survey, 1869-1879.

3. The Red River Expeditionary Force, 1870

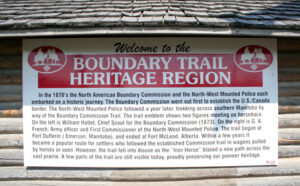

4. Her Majesties North American Boundary Commission, 1872-74

5. North West Mounted Police ‘Trek West’, 1874.

***

1. The British North American Exploring Expeditions, 1857-59.

Canadian – Hind Expedition June 23, 1858 campsite on the banks of the Assiniboine River .

The monopoly of the Hudson’s Bay Company to exclusive trade in the British Northwest Territories was due to expire in 1859. The company wished for an extension of its monopoly, but the Canadian government indicated to Britain that it was extremely interested in extending its administrative jurisdiction over the interior. “Settlement of the interior and a communication link over all the British possessions in North America seemed desirable imperial goals, but their feasibility was uncertain without more thorough investigation of the area.” (Huyda 1975:3)

There were several reasons behind the British and Canadian governments sponsoring of exploring expeditions into the Western Interior. There was growing imperial concern for more secure links with the far western colony in British Columbia, where gold had been discovered. Also the Pacific coast was of growing importance to British trades interests due to the growth of trade with the Orient. In the interior, the small settlements along the Red River had been growing slowly, and it was undesirable that they should remain isolated and exposed to the American westward expansion. Trade and transportation ties between the Red River and St. Paul, Minnesota had been growing since the 1840s when American steamboats, and then railways, reached north from Chicago into Minnesota. The growing closeness between Americans and the Red River Settlement, coupled with a lack of an all-Canadian route to the west, threatened the security of the entire British Northwest Territories.

In 1857, two exploratory expeditions were sent to the western territories for the purpose of providing their respective governments with “an accurate objective description of the geography…and the resources of the area, to assess the agricultural, and settlement potential, and to report the possibilities of a permanent communications route linking all the British North American colonies.” (Huyda 1975:3)

Captain John Palliser, a British Army Officer, was placed in charge of the British Expedition. He spent three years, from 1857 to 1859 exploring the western interior. His explorations took him along the Red River Valley to the international boundary at which point he turned west and travelled along the 49th parallel through the Turtle Mountains. It has been claimed that he followed a route which later became a section of the Commission Trail, and his journal seems to confirm this: We arrived at the brink of a wide valley through which the Pembina River flows. The descent to the river margin is very precipitous, but there is a tolerably good road winding through coarse wood, formed by the hunters, who resort annually to the plains beyond.“ (VoI 1, pg. 205.)

The Canadian Expedition was headed by Professor Henry Youle Hind, a professor of chemistry at the University of Toronto. During the summer of 1857 the expedition explored the district between Lake Superior and the Red River, determining the best path of an all-Canadian route to the Red River. Simon Dawson (1820-1902), a Scottish-born civil engineer was in charge and laid out the route of Dawson Trail, which early settlers from Ontario would soon speak of in derision.

During the three months of the 1858 survey, Hind’s team was divided into two parties. Simon James Dawson, a Scottish-born civil engineer, conducted his survey north from Portage la Prairie. Hind explored to the south, to the west up the Qu’Appelle River valley, and to the northwest as far as the South Saskatchewan and Saskatchewan Rivers. After leaving Red River on June 15, Hind’s division (including fourteen men, six Red River carts, and fifteen horses), travelled up the Little Souris River, below present-day Brandon, Man. He had James Austin Dickson as his surveyor and engineer, John Fleming as assistant surveyor and draughtsman, and Hime as photographer. The summer of 1858 was exceedingly dry and their impressions of the land south of the Assiniboine River was generally negative. Hind noted they had travelled through a country whose “general character is that of sterility” (Vol. I, pg:285). On June 27, 1858 they ascended “the last of the Blue Hills”, near modern Margaret, Man. There, they looked out onto, “one of the most sublime and grand spectacles of its kind . . . a boundless level prairie on the opposite side of the river, one hundred and fifty feet below us, of a rich, dark-green colour, without a tree or shrub to vary its uniform level.” (VoI 1, pg. 291).

As a result of the Canadian Exploring Expedition’s glowing reports about the Pembina Hills – Turtle Mountain region, and of the whole prairie parkland region in general, increased interest in the West developed in Colonial Canada. The reports of the Canadian and British Exploring Expeditions were to form the basis of the Canadian Government’s plans for the transcontinental railway and the subsequent settlement of the west.

For more information and stories about the British North America Exploring Expeditions 1857-1860, click the links below:

- Ft Garry to Ft Ellice via Turtle Mtn, Palliser, 1857

- Ft Garry to Ft Ellice via Souris River, Hind, 1858

- John Fleming – Canadian Expedition Sketch Artist 1857-58

***

2. The Dominion Land Survey, 1869-1879.

The Boundary Trail Heritage Region and adjacent areas played a pivotal role in the new Dominion government’s herculean task of surveying the entire British northwest territories as an important precursor to agricultural settlement. The entire current ‘Section-Township-Range’ system of rural land survey in western Canada is directly connected to a single point on the International Boundary about 22 kilometers west of Emerson – a point somewhat arbitrarily chosen by the the first Dominion Survey crew during the early summer of 1869. The Dominion Survey would progress east, west and north from that point to cover essentially all of western Canada.

The Parish River-lot Survey System

The first system used to demark and describe land parcels in what is now Manitoba was proposed by Lord Selkirk for use by the Selkirk Settlers, and was based on the Québec long-lot system. Two-mile long, (3.2 km) narrow lots, fronting on the Red River, came to be the standard type of land parcel in the Red River Colony. Divided into ‘parishes’ with a centrally located church, the system was retained when the Dominion ‘section’ Survey commenced in 1869, and was even expanded up the Assiniboine River as far as Portage la Prairie, and up the Red River as far south as the American border.

The Principal Meridian and the Start of the Survey

The Dominion Survey in western Canada began in the spring of 1869, in preparation for the transfer of the territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company to the Dominion of Canada. The first line to be staked out was the Prime or Principal Meridian, which runs in a straight line due north from a point selected somewhat arbitrarily by the survey team, on the international boundary some 23 kilometres (14 miles) west of the present community of Emerson The purpose was to ensure the Prime Meridian did not intersect the two-mile-wide river-lot survey along the Red River at its most westerly point near present day Morris.

The Prime Meridian, or Principal Meridian is the baseline from which all of western Canada was subsequently ‘sectioned-off’ into square ‘townships’; each comprised of 36 one-mile square ‘sections’. The townships were numbered according to their position north of the United States border and east or west of the Principal Meridian. Each section was divided further into ‘quarter sections’ of 160 acres each. The standard ‘homestead claim’ consisted of a quarter section – which could be obtained for a ten-dollar administration fee and meeting residency and land improvement requirements.

The Township Grid

The Dominion Survey system, with its ‘Section, Township and Range’ coordinates, was quite different from the ‘County’ and ‘Long Lot’ systems used in Ontario and Québec. The Dominion Government wanted a quick and effective system for partitioning and administering the land, thus facilitating the rapid settlement and development of the Canadian Prairies, and with the revenues created help to pay for the construction of the CPR. The Township system ultimately used was based on the system the Americans incorporated in the settlement of the US Mid West, with some minor adjustments, particularly the inclusion of a 99-foot road allowance around each section. At first, it was intended that each township would consist of 64 square-mile sections, so that they would be large enough to serve as local government units. This ‘large’ township survey was used during the first summer of surveying, in 1869. Before long, however, the decision was made to use instead the smaller, American-style, 36-section-sized townships.

1. larger 800-acre sections, rather than 640 acres;

2. long-lot quarter sections, with quarter-sections 1/8 by 1 mile in size, rather than ½ by ½ mile square; and

3. various patterns and widths of road allowances within each township. Several railway and government officials also suggested several rather imaginative township plans, which were never implemented.

***

3. The Red River Expeditionary Force, 1870

The Canadian Government decided early in 1870 to send a military expedition to Red River because of the disturbed state of the Red River Settlement resulting from the transfer of Rupert’s Land to Canada. This expedition of brigade strength was under the command of Col. Garnet Wolseley (later Viscount Wolseley) of the Imperial Army. The force was composed of three battalions, one from the British regular army garrisoned at Quebec, a few Royal artillerymen, and two Canadian militia battalions, consisting in all of approximately 1450 men.

The most direct route to the Red River Settlement from Canada was through American territory, but the US government refused to grant passage to armed British and Canadian troops. As a consequence, the expedition faced an arduous journey across the rugged wilderness of the Canadian Shield following the old fur-trade route west from Lake Superior to the Prairies via Rainy River, Lake of the Woods, Winnipeg River and Lake Winnipeg to the mouth of the Red River. The expedition is considered by military historians to have been among the most arduous in history.

Over 1,400 men transported all their provisions and weaponry, including cannons, over hundreds of miles of wilderness and traversed 42 portages. Expedition members cut trails through seemingly endless forests, laying many miles of corduroy roads and erecting dozens of timber bridges. In addition to quelling the Red River Resistance, this road building work was because of instructions to the Wolseley Expedition to construct an “all Canadian route” to the newly-acquired Northwest Territories along the route first surveyed by the Hind Expedition a decade earlier. As these jobs were being done, the troops had to endure life in the bush, the summer heat and plagues of blackflies and mosquitoes.

The expedition left Toronto May 10, 1870 and reached Fort Garry four months later on August 24. Their approach had been observed and, when they arrived, they found that Riel and his lieutenants had departed leaving the fort essentially deserted. So ended the Red River Expedition, rather anti-climatically and without a single shot being fired. Wolseley himself stayed for only a few days, returning to Eastern Canada with his regular forces undertaking another laborious journey over the route they had just come. Wolseley left a provisional force in Manitoba made up of the militia battalions, who went into garrison for the winter. This force was relieved by the Provisional Battalion of Rifles that came in 1872, followed by a third contingent to come to Red River. The continued presence of a militia force was meant to counter growing American annexationist interest in the Red River settlement, especially as the Dominion government was unsure of the loyalties of the local Métis, Country Born and Aboriginal residents. This proved to be counter-productive as militia harassment of Métis during this period exacerbated already intense feelings and assaults and at least one Métis death resulted. Nevertheless, with the active involvement of Bishop Taché in negotiations with the federal government, in 1870, Manitoba became the first western province to join Confederation. Despite this, the Red River Expeditionary Force was not formally disbanded until 1877.

The sudden departure of Riel and most members of his provisional government in the autumn of 1870 effectively ended the so-called Red River Rebellion. This left the men of the expedition free to return to their homes in Ontario and Quebec. Many did so; however, expedition members were rewarded for their service with free homesteads of any surveyed and available lands. A considerable number remained, or later returned, and became important elements in population of the new province and western Canada. One of the most prominent was Hugh John MacDonald, only son of Prime Minster Sir John A. MacDonald. He was a member of the 1st Ontario Rifles and later premier of Manitoba. Private William Alloway, 2nd Battalion Quebec Rifles, became one of the first and most successful banking firms in Winnipeg. Another veteran of the force, Judge John Walker, was elected to the provincial legislature and later became a provincial court judge and provincial attorney general. Other members of the force went on to distinguished careers in the NWMP including Captain Wm. Herchmer, (Ontario Battalion), and Captain MacDonald and Lieutenant Jack Allan, (2nd Quebec). Captain Herchmer was involved with the International Boundary Commission in 1872 and 1873; became Commissioner of the NWMP in 1886, and served in the South African War in 1900.

In rural Manitoba, members of the force were outstanding pioneers of several communities. The Pembina Mountain Country, for example, Thomas Cave Boulton was its first permanent settler, a member of the Expeditionary Force,. The wide open life of the prairies had gotten into his blood, so he in 1872 he returned west and established his homestead along Silver Creek in what later became the Nelsonville area. Other members of the Wolseley expedition who became neighbours of Boulton included John Cruise and Charles Viney Helliwell of the 2nd Battalion Quebec Rifles. Descendants of another member of the Wolseley Expedition are still living in the Manitou district. Samuel Forrest, from Renfrew, Ontario, came to Manitoba as a voyageur with the force. He returned to Renfrew; however, in 1879 came back west and took up a homestead in the New Haven district, northwest of Manitou.

F.J. Bradley, first inspector of customs at the HBC post at North Pembina, (later West Lynne), was himself not a member of the Wolseley Expedition, but his brother-in-law and partner in several business enterprises, Dr. Alfred Codd, was. After the return of the Red River Expeditionary Force, Surgeon Major Alfred Codd was appointed to take charge of the provisional battalion formed to garrison Fort Garry and continued his services for many years as senior medical officer for Military District No. 10. Several of the first residents of the Emerson community and neighbouring districts also came out with this force, William Nash being one of the most prominent. He served as Ensign of No. 1 Company of the 1st Ontario Rifles and having previously served in Ontario expelling the Fenian Raid of 1866. He later served in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 as a Captain in the Winnipeg Light Infantry and was promoted during the campaign to the rank of Major. In civil life, Major Nash was a solicitor and barrister and the first member for Emerson in the Manitoba provincial legislature. He later became Registrar of Deeds in Emerson and later accepted a position in the Land Titles Office in Winnipeg.

Manitoba Fenian Raid of 1871