RCMP HERITAGE STORIES

RCMP Quarterly October 1941

The Historic Forty-Ninth 54*40’

By John Peter Turner

Sixty-nine years ago a band of men laboured and toiled westward along the 49th parallel into an unsettled land. And out of their work evolved the most friendly boundary in existence – the line between Canada and the United States.

Disputes concerning international boundaries clutter the pages of history.

Difficulties bearing upon territorial limitations have resulted in countless wars and the dissolution of many dynasties. But resort to arms for the purpose of establishing tangible or imaginary walls between territorial claimants has not always followed. Goodwill, equitable interchange of human energies, co-operation, trust – these are a few of the inevitable blessings that have accrued from well-defined and well-respected boundaries. Nowhere has this been more fully exemplified than in the New World. No international demarcation stands more firmly rooted or enjoys more wholesome respect than the border line between the Dominion of Canada and the United States.

Happily, there have been no Maginot or Siegfried lines in North America.

The story of the actual marking of the 900-mile link from Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains by the North American Boundary Expedition of 1872-4, is one of remarkable foresight, unbending courage and high achievement.

* * *

To look back. Upon the completion of the ‘Louisiana Purchase,’ in 1803, the boundaries of the vast territory thereby ceded to the United States presented a geographical problem. Subsequently, in an endeavour to arrive at a definite solution to the vexatious question, it was claimed that, by the Treaty of Utrecht, concluded in 1713, the 49th parallel of latitude had been adopted as the dividing line between the old French possessions of the west and south and the British territories of Hudson Bay on the north. Concerning the limitations of the vague, unknown Louisiana, especially beyond the Rocky Mountains, no-one could speak with finality. There were the unsettled claims of Spain, Russia, and Great Britain besides those of the United States. The latter proposed, as a basis from which to work, that the dividing line should run from the north-western extremity of the Lake of the Woods, north or south as the case might require, to the 49th parallel of latitude, thence to the Pacific. At the convention of London, Oct. 20, 1818, the commissioners appointed respectively by Her Britannic Majesty and by the President of the United States agreed to admit this line as far west as the Rocky Mountains.

Negotiations bearing chiefly on the regions of the Pacific were carried on over a period of years. In 1845, the British minister at Washington suggested a completed east and west line which would have given Great Britain two-thirds of Oregon, including the free navigation of the Columbia River.

This proposal was promptly rejected, and no further attempt at adjustment was made until the next year. President Polk then insisted that the boundary should be fixed at 54* 40’. An animated debate on the subject began and lasted until near the close of the Washington session of 1846, and the question lost most of its national importance in bitter party conflict. An election was pending. Most of the Democrats adopted the recommendation of the President, and coined the defiant cry: ‘Fifty-four forty or fight!’ This ultimatum caused a few leaders of the government party, of whom Col Thomas H. Benton was perhaps the most prominent, to unite with the opposition.

Finally, that same year, a treaty was signed and the 49th parallel became the international boundary.

Meanwhile, as a result of the Oregon dispute, the British Government sent out a military force ‘for the defence of the British settlements.” These troops – 347 regulars under Major Crofton – were made up of a wing of the 6th Royal Regiment of Foot, a detachment of Royal Engineers and some artillery. The traditional redcoat was thus introduced to the plains. Some of the men were stationed at Fort Garry (the embryo Winnipeg) on the Red River and the others twenty miles down the stream at Lower Fort Garry, known also as the ‘Stone Fort’. These troops returned to England in 1848.

In 1870, Canada completed the purchase of the great realm of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company. The time had come for the marking of the Canada-U.S. boundary and the establishment of law and order in the West. Two years later arrangements were made with the United States for the survey and demarcation of the line; and the following year, 1873, was to witness the formation of the North West Mounted Police.

* * *

In 1872, under the titles of ‘Her Majesty’s North American Boundary Commission’ and ‘United States Northern Boundary Commission’, a dual organization was set up by Canada and Britain on one side and the United States on the other. These commissions were to cooperate in locating and marking the line agreed upon.

The Canadian Commissioner was Capt. Donald Roderick Cameron, R.A. (later major general, appointed in 1888 to the command of Royal Military College at Kingston; a son-in-law of Sir Charles Tupper, Prime Minister of Canada, 1896). He was supported by four officers of the Royal Engineers: Capt. Samuel Anderson, Chief Astronomer, who had seen service at Greenwich and taken part in the survey of the boundary between British Columbia and the United States years earlier; Capt. Featherstonhaugh, senior officer to Anderson; Capt. Arthur C. Ward, Secretary and Paymaster; and Lieutenant Galway. In addition there were sub-assistant- astronomers Coster, Ashe, George F. Burpee, and W. F. King (subsequently International Boundary Commissioner). There were two principal surveyors, Lieutenant Colonel Forrest, Commandant of the Ottawa Garrison Artillery, and Alexander Russell, brother of Deputy Surveyor – General Lindsay Russell. L. A. Hamilton, who years later was to map out the town-site of Vancouver and become land commissioner of the Canadian Pacific Railway, served as assistant surveyor. Dr. Burgess, his assistant Dr. Millman, and veterinary surgeon George Boswell were also members of the staff. A company of Royal Engineers served in various capacities. Occupational positions were filled by nearly three hundred young Canadians and Old Countrymen. A corps of mounted scouts, composed chiefly of half-breeds served under William Hallett, a famous Scotch Metis from Red River.

The United States Commission employed about 250 civilians under Archibald Campbell who had been a commissioner in the survey of the British Columbia – United States’ line. Other officers were Lt Col F. M. Farquhar, Chief Astronomer, who was later succeeded by Capt. W. J. Twining; Sub-Astronomer Captain Gregory; Lieutenant Green of the U. S. Engineers, Chief Surveyor; and J. E. Bangs, Secretary. Dr. Elliott Coues acted as geologist and naturalist. In addition to two troops of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, there were five companies of U.S. infantry acting as escort.

* * *

Actual field work commenced in September, 1872. By pre-arrangement, the line was run eastward from the Red River to the Lake of the Woods mostly by the British party. Advantage was taken of the late season to negotiate the many muskegs and swamplands encountered. East of the Roseau River, through the forested country strewn with windfall, brule and rock, dog-teams and snow-shoes were the principal means of travel. The winter was exceptionally severe and the hardships were extreme. Quartermaster, Capt. Lawrence Herchmer, late 15th Regiment (fourth commissioner of the North West Mounted Police, 1886-1900), had his hands full keeping two supply posts and scattered parties replenished from the main depot at Dufferin.

Upon reaching the Lake of the Woods the boundary as defined by treaty was found to turn north-east to the North-west Angle, where boundary commissioners under the Treaty of Ghent, 1814, had terminated their labours in 1825. In determining the point where the 49th parallel strikes the western shore of Lake of the Woods, there was a difference of only twenty-eight feet between the findings arrived at by the British and U.S. astronomers; as a consequence the middle point was accepted as correct. During the winter two men lost their lives, one from exposure, the other by a falling tree.

The survey parties returned to the Red River in the latter part of February, 1873, having completed the first part of the work.

On the west bank of the river, a short distance north of the boundary and from the old Hudson’s Bay post of Fort Pembina, commodious buildings for the Canadian headquarters had been erected under the supervision of Captain Wards. Near-by was the present town of Emerson, at that time known both as North Pembina and West Lynne; and just south of the border was the U.S. army post also called Fort Pembina, headquarters of the United States Commission.

The new settlement at the Canadian headquarters was named Dufferin in honour of the Governor General of Canada then in office. Facing the river was a large house used as offices, living quarters and mess room for the staff, who were billeted in several one-storey dwellings. Other buildings housed mess room and kitchen, barracks for the engineers, surveyors, astronomers, photographers, axe-men, harness-makers, wheel-wrights, cooks, picket men, blacksmiths and carpenters.

A farm was established where all necessary produce was grown for men and horses. A canteen was stocked with the best of liquors, imported duty-free direct from England; all brands were sold at the moderate charge of five cents a glass. Crosse and Blackwell’s potted meats and pickles and many other luxuries were obtainable. Weekly, each man was rationed at plug of T&B smoking tobacco and three plugs of ‘chewing’ if he wished it. All profits from the sale of ‘extras’ went towards a library. The food was of the best quality. Supplies were brought in from Moorhead, 150 miles south in Minnesota, and from Fort Garry, sixty miles north. So efficiently was at the commissariat handled by Quartermaster Herchmer that complaints were unknown. Necessary articles of clothing could be purchased cheaply.

Buckskin and leather clothing, moccasins and woollen mitts were issued for winter use; and as bedding, each man received a large oilskin sheet, a buffalo robe, and two pairs of ‘four-point’ Hudson’s Bay blankets.

In the winter of 1872-3 a grand dance and feast was given in honour of the Canadians by Commissioner Campbell and his staff at the U.S. army post. Later the same winter a similar compliment was paid the Americans on the Canadian side. Both events were attended by many guests including the fair sex from Fort Garry. In season there was hunting, skating, snow-shoeing, boxing matches, an occasional theatrical, and other diversions.

* * *

In April, 1873, preparations began for the greater part of the work. Enough men, horses, oxen, wagons, equipment, regulation army tents, instruments and provisions had been carefully assembled.

The Dominion Government had deemed it advisable that the Canadian part of the expedition should move through the Indian country without show of force. It would have been unwise for the British party to travel through the United States as, in that event, the Indians would have had no visible evidence that British interests were distinct from those of the United States. Although every member was furnished with arms and ammunition, there was no display of special precautionary measures. Parties and individuals prosecuted their work and hunted on the prairie without apparent fear. No escorts were in evidence. Indians were given free access to the camps.

As any time the natives might have sacked supply stations, have necessitated a concentration of the labourers, and generally delayed operations; but it had been felt that a friendly attitude and good behavior by the expedition would obviate these possibilities.

Conversely, the United States Commission, because of the Indian wars raging on the trans-Mississippi and Missouri plains, saw fit to travel under military escort.

As the prairies stirred beneath softening winds, a start was made. To the west lay a savage land. This way and that, the eye rested upon space. The wooded course of the Pembina River paralleled the line of travel along the south, and far ahead rose the Pembina Mountain. League on league of virgin soil, that down the centuries had put forth naught but successive growths of grass and flowers, spread westward.

Like a ship at sea the joint expedition travelled mostly by observation, marking the boundary as they progressed. Astronomical stations and supply depots were established. Cattle were driven to furnish meat until the buffalo country could be reached. A road-making party, preceded by native scouts, went ahead of the main body. Rivers that were not fordable had to be bridged, often necessitating wide detours to obtain suitable timber for the purpose. A chain of field depots, strategically placed to ensure wood and water, was thrown out from the main station at Dufferin.

The first of these depots was erected about forty miles west of the Red River at the Pembina Mountain; others were located at irregular intervals as the work proceeded. There were few dry camps. Barrels, mounted on wheels, carried a water supply over the arid districts. Half way to the Pembina depot at an astronomical station known at Point Michel, observations taken by both parties to determine the parallel gave a difference of seven feet; sixteen miles further west there was a difference of twenty seven feet. These results were considered satisfactory, the difference being divided; and the central point in each case was assumed to be on the true 49th. The greater part of the line was determined in this way. Tangents of approximately twenty miles were taken turn about by the Canadians and Americans. The working parties on both sides were kept as much as possible within a distance not exceeding sixty miles of one another. Considerations of supply and the presence of Indians forbad any greater extension.

In the swampy country from Lake of the Woods to the western boundary of Manitoba, iron pillars were placed at two-mile intervals as nearly as the nature of the ground would admit or at such sites as were available.

Westward from Manitoba to the line previously run and marked from the Pacific coast, stone cairns or earthen mounds were constructed about three miles apart. Buried in their centres were iron tablets bearing the inscription ‘British and United States Boundary Commissions, 1872-74, 40 (degrees) north latitude’. Square posts four feet high and tapering at the top were also used. These were sunk six feet in the ground having a flange at the bottom to ensure stability. On the north side each post was marked ‘British Possession’, on the south ‘U.S. Territory’.

To provide for the possible disappearance of monuments and the definition of the line in intervening spaces, Commissioners Cameron and Campbell agreed that the line between neighbouring monuments should be held to run from point to point of the astronomically determined 49 (degrees) north latitude, following the course of a line having the curvature due to a parallel of that latitude.

It had been arranged that throughout the entire distance topographical surveys extending six miles north and south of the boundary would be made by both commissions. By pre-arrangement, an exhaustive collection of western birds was gathered for the British Museum by Prof. Geo. M. Dawson, Geologist of the Canadian Commission, who also reported upon the resources of the region traversed.

Over the well-marked trail of the advancing expedition, covered wagons in horse and ox trains and Red River carts driven by half-breeds continually freighted the Canadian supplies from Dufferin. The American provisions were drawn by bull and mule teams from various trading posts on the Missouri River. Oats for the many horses constituted a large part of the shipments.

The first important halt was made after a strenuous period of axe-work across the Pembina Mountain; and a supply depot was established near the Pembina River. Game abounded. A moose hunt was staged. Prairie chicken and wild duck were served at every meal, until the exasperated cooks insisted that the plucking should be done by those who wanted birds on their bill-of-fare.

From the Pembina depot the line of travel took the survey past the White Earth and Badger Creeks.

A monotonous region stretched ahead. Clouds of grasshoppers swarmed upward with crackling sound; mosquitoes and bull-flies tormented man and beast. Bleaching skulls and bones of buffalo littered the ground. Stunted grasses clothed the rolling uplands; no trees worthy of the name relieved the dreariness. But as days passed, a blue outline resembling a low-hung cloud, which proved to be Turtle Mountain, appeared in the south and west. A large depot was established there. The line now ran directly across brush-clad hills in which were many lakes and creeks literally filled with wildfowl. Many deer were seen; some were killed.

The expedition came upon a large camp of Sioux. The chief was friendly and addressed himself to Commissioner Cameron in peaceful terms.

“I am Weeokeak, head of a hundred lodges – the Waughpatong band of the Dakotas – son of a great chief. I am glad to see the English. I would like to smoke with any English chiefs I might meet, and would be thankful for food and ammunition. The Canadians and English I respect; and I would be very glad of anything they give me. We all wish for a piece of English ground.”

A wide expanse was next traversed to the Souris River, where three days were spent in making bridges. For this purpose the Royal Engineers constructed coffer-dams and floated them out to be filled with stones. While crossing the stream in the army ambulance drawn by four mules customarily used by Commissioner Campbell, several officers of the U. S. Commission narrowly escaped calamity when the conveyance upset.

The featureless terrain spread onward to the second crossing of the Souris beyond which towered the Hill of the Murdered Scout. According to legend, a Cree scout had been watching for Mandan enemies from this conical butte. Tiring of his vigil he stretched out and slept. A Mandan who had been spying from another vantage point stole upon his sleeping foe and brained him with a large stone. In commemoration the Crees had carved in the turf at the top of the butte a giant figure of a man with arms and legs outstretched. They placed a large boulder near-by and cut a long series of footmarks in the hillside to indicate the Mandan. Each year, these cuttings had been renewed to perpetuate a fanciful twist of Cree mentality. Thus the butte gained its picturesque and lasting name.

A few miles westward just north of the boundary, the remarkable Roche [Percee] rose abruptly. Its fissured sides were scored with native figures and hieroglyphs; to these were added the names and initials of several men of the 7th U.S. Cavalry who, under General Custer, were fated to fall in the battle of the Little Big Horn, 1876.

Nine miles beyond at a favorable location significantly called Wood End, another depot was placed near a plentiful supply of coal which was used to good account in the camp kitchens and portable forges.

Athwart the entire range of vision to the west spread a stupendous upland – the Grand Couteau du Missouri. In addition to the depots at Pembina Mountain, Turtle Mountain and Wood End, seventeen temporary astronomical stations, observed by the joint commission, had been set up at Lake of the Woods (joint), Pine River, West Roseau Ridge, Red River (joint), Pointe Michel (joint), Pembina Mountain, East (joint), Pembina Mountain, West, Long River, Sleepy Hollow, Turtle Mountain, East, Turtle Mountain, West, 1st Souris (or Mouse River), South Antler, 2nd Souris (or Mouse River), United States’ No. 8 Astronomical Station, Short Creek and 3rd Mouse River (Wood End). And more than four hundred miles of arduous work had been completed.

Summer was over; winter was fast approaching. The commissioners gave orders to return, but a snow-storm delayed departure for more than a week. During these idle days, the weather-beaten men waited impatiently, eager to return to the Red River. Yet eagerness was tinged with speculation. Adventure beckoned. The next spring would see them back to continue the task. They would then discover the secrets of the rolling heights that lay ahead.

What revelations and experiences awaited in the Great Beyond? The following year would tell.

Continued RCMP Quarterly January 1942 p 270-281

The preceding instalment of this article traced the initial evolution of the western portion of the boundary between Canada and the United States. The final stage is here recorded – a brief story of full cooperation between two great friends, who today, with combined resources and regardless of boundary, stand shoulder to shoulder against tyranny and barbarism.

The work on the international boundary had been well advanced. Approximately half the long line of nine hundred miles between the Lake of the Woods and the Rocky Mountains had been surveyed and marked in 1873 by the Canadian and United States joint commission.

The two great Anglo-Saxon countries of North America, in keeping with the spirit of the Oregon Boundary Treaty (1846), had extended their interests westward in full harmony and cooperation. The 49th parallel was on the way to becoming a symbol of peace and concord, an example to the remainder of the world.

Though separated in their respective quarters at Dufferin and South Pembina, the men of the surveying parties under Commissioners Cameron and Campbell lived almost as one community during the winter of 1873-4. Despite the isolation, there was no lack of diversion. The months passed pleasantly in a continual round of card parties, dinners, dances, get-togethers, sing-songs and various outdoor sports. A free and easy cordiality prevailed and even the natives participated in the dances. In addition there was considerable visiting back and forth in the growing Manitoba town of Winnipeg (Fort Garry) to the north, the neighboring Dakota and Minnesota settlements and the big north-western town of St Paul several hundred miles away at the head waters of the Mississippi.

In the spring all was bustle and activity.

William Hallett, the trustworthy Scotch half-breed who had been in charge of the scouts the previous year, was forced to retire. He had grown too old. Captain East, R.A., was commissioned to engage forty experienced plainsmen who were to ride in advance of the expedition and report on the country – give the location of streams, lakes, pasturage and wood; and most important of all perhaps, to act as intermediaries in the event of trouble with the Indians.

All established depots between the Red River and the Great Couteau were replenished with supplies and made serviceable. A reconnoitring party, accompanied by a commissariat train, was sent forward to build a substantial depot at Wood Mountain. And before summer was under way all hands were busy continuing the line beyond Wood End.

It was known that a veritable realm of savagery lay ahead. On the plains north of the ‘forty-ninth’ probably thirty thousand Indians lived, hunted buffalo and intermittently waged inter-tribal war. In addition to the great Blackfeet Confederacy – Blackfeet, Piegans, Bloods and Sarcees – wandering bands of Plain Crees, Assiniboines and Saulteaux occupied the country to the west. Except for the widely-separated Hudson’s Bay Company posts and a few scattered half-breed traders trafficked for the produce of the buffalo ranges, and a few missionaries who strove to gain dark-skinned proselytes, the red men were the only inhabitants of the interminable grasslands.

South of the international line, Indian warfare was being waged continually and the scanty white population was running free of the restraints of established authority. Strategic points were garrisoned by soldiers. The westward march of civilization to the trans-Mississippi plains had rendered the Indian lands valuable; and, despite treaties between whites and aborigines, the red men, like the buffalo, were forced to seek sanctuary wherever they could find it. Concurrently, men whose misdemeanours had driven them far out the western trails had come northward into Canada.

The great Sioux nation was all powerful along the river highway of the Missouri, the natural outlet to the West. But bad elements from the east, any of the men and women ‘on the dodge’ who sought exception from the clutches of the law, were in the ascendancy. Ever westward an army of occupation was pressing on. A colossal movement had been launched, a hegira before which all native life faced complete forfeiture of its primordial ways, a wave of bloodshed in which brave men laboured to establish law and justice and liberty in the face of debauchery, breach of trust and murder. An American saga was being written. Outrages by desperadoes, hideous massacres, heroisms, crowning adventures, and violent deaths were commonplace.

These conditions had reached British territory. Liquor had come from the Missouri to the Blackfeet country, where it was said strongholds had been erected to gather spoils from the Indian hunters.

The West was running wild, probably wilder than before the coming of the white man. Flaming colours were being added to the story of a great transition.

For more than six hundred miles across this last retreat of Indian life, the huge glacial moraine of the Missouri Couteau saddled the plains from north-west to south-east. Awesome, treeless and windswept, its interminable undulations, given over to wolves, birds of prey and wandering nomads, seemed like a land beyond the world. And into it penetrated the surveyors of the boundary.

Many days were needed to cross the dreary uplands of the Couteau; finally however as a climax to a scene which had become irksome, the toilers reached a river valley, gloomy and uninviting in its general aspect and devoid of vegetation. Probably the Big Muddy. The surveyors continued on, passing several branches of the Poplar River. Gradually the surroundings improved; and soon, to the relief of all the Couteau lay behind. Wood Mountain loomed ahead.

Midsummer came bringing another important movement on the plains. The North West Mounted Police, three hundred strong, had assembled at Dufferin late in June preparatory to its epic march westward. The Canadian Boundary Commission buildings had been adopted temporarily as a headquarters and stepping-off point; and, travelling faster than the surveyors, despite cumbersome transport and ‘beef on the hoof’, the newly-organized Force had taken a course northward of and paralleling the boundary. As the slower-moving surveyors were overtaken, supplies threatened to run short, and the commissioner, Col. George A. French, decided to seek assistance from the nearest settlement. Making a detour from the line of march and reaching Willow Bunch, a small half-breed community nestled in the folds of Wood Mountain, the assistant commissioner of the little red-coated army, Major James F. Macleod, accompanied by five men and six Red River carts, purchased a quantity of buffalo pemmican and dried meat from the half-breed traders at that point. Shortly afterwards, he transported a needed supply of oats to the Mounted Police from the surplus stores in the boundary commission depot at Wood Mountain, and arranged for an additional amount to be furnished as required. The following year, the buildings at this depot became the Wood Mountain Detachment of the Mounted Police.

Meanwhile the boundary commissariat, under the able direction of Capt. Lawrence Herchmer, had functioned capably and had tended to sustain a fine esprit de corps among the men. Though the food was rough, it was of the best procurable in this distant land. ‘Buffalo chips’ – the dried dung of buffalo – served admirably as fuel, especially on the Couteau where there was a marked scarcity of wood, and the water carts off set the misery of dry camps.

Soon after leaving Wood Mountain depot, buffalo were sighted for the first time – a small herd browsing quietly on the side hills of Cottonwood Coulee. Antelope was plentiful. By the sparkling waters of Frenchman’s Creek, one of the most attractive camp-sites of the entire undertaking awaited the men. This locality was to furnish a rendezvous for Sitting Bull’s refugee Sioux in 1876-7 after the Custer Massacre south of the boundary.

The surveyors spent several days here resting the horses, washing, and making everything shipshape. Here also they had their first meeting with the Indians of the farther plains. A few miles down stream, an adventurer named Juneau operated a small trading post; nearby was an encampment of about forty lodges of Sioux.

The red men received the white visitors with obvious delight, doubtlessly expecting some favours; in turn they visited the boundary camp and were reassured when they received an affirmative reply to their questions, “Are you the King’s men?” Apparently they referred to Kind George III. Their forbears had been allies of the British troops, and their chieftains had received medals for their services; but, of more significance, they had gained a lasting respect for the red-coated servitors of the King. They proferred buffalo tongues as special gifts to the surveyors and provided them generously with fresh meat.

“In another two days of travel,” the feathered and painted Sioux told the white men, “you will find the buffalo thick upon the plain.”

The expedition was reluctant to leave this pleasant camp. But it was imperative they push ahead. Crossing the east and west forks of the Milk River, they encountered more badlands. Here the buffalo were amazingly plentiful. Every slope lay sprinkled with white skulls and skeletons – a slaughter field for centuries. To the westward, a long blue shadow appeared, but instead of the hoped-for Rocky Mountains, it was soon discovered to be the unmistakable Three Buttes of the Sweet Grass Hills, shown on Palliser’s map.”

The travellers scanned the prospect in silence. Here was utter loneliness – a high, open plateau broken at intervals by some river-bed, or deceptive hollow, where a man, a hundred men or a herd of buffalo could disappear in a moment. Little did the spectators realize that a few miles away the bewitching fastnesses of the Cypress Hills, with their infinite variety of forest and glade, lush meadows and tumbling brooks – a paradise of natural beauty -, rose from the encircling prairies. It was there that a fiendish butchery of Assiniboine Indians by Missouri desperadoes had occurred in the previous spring, a base episode that had hastened the formation of the North West Mounted Police.

Slowly but steadily the combined survey parties progressed towards the farther plains, meeting small bands of Indians almost daily. And presently, as the main stream of the Milk River was crossed, the Sweet Grass Hills loomed more distinctly.

The travellers were now in the ‘Land of Painted Rocks,’ where, according to Indian legend, the spirits of the departed dwelt. Here, amid scenes where they had fought, hunted, performed their strange rituals and passed to the Happy Hunting Grounds, the ghosts of by-gone red men were wont to return and camp among the strangely-moulded and painted rocks. To the Blackfeet, this was holy ground; Writing-on-Stone, they called it. Tribal incidents were crudely etched on the faces of grotesquely-shaped cliffs. Decked in a thousand shades, this region of Nature’s caprices was strangely beautiful as sunlight and cloud, alternately, played upon it. At close of day, it was as uninviting as might be a part of Hell with the fires burned out; in darkness, it was a nightmare land of bleakness and weird configurations.

Almost on the line of demarcation, the Three Buttes, towering several thousand feet above the plains, and surrounded by deep-cut coulees and broken lands, now loomed in majestic outline. While exploring the vicinity several of the men came upon the bodies of many dead Indians. All had been shot. One corpse bore sixteen bullet wounds. Near-by were small pits strewn with empty cartridge shells as though a defensive battle had been waged. It was learned later that the dead were a band of Crows from the Missouri country who, while on a horse-stealing foray, had been ‘clean out’ by Piegans.

Onward past the Three Buttes the surveyors pressed. And now the snow-capped peaks of the Rockies could be seen, a hundred miles away. The magnificent Chief Mountain showed distinctly, its gigantic sugar-loaf top a distinguishing landmark among its fellows. Buffalo, in prodigious numbers, roamed freely. Little exertion was necessary to kill one or more at any hour of the day; and carcasses, shorn of their skins, lay everywhere.

Beyond the last crossing of the Milk River the land gradually ascended to the foothills. A few miles further west the travellers came to the St. Mary’s River, which presented the most fascinating and picturesque scene yet reached. Use was made of coal deposits found on its banks. Down stream, near the present site of Lethbridge, Nick Sheran, an Irish-American from New York, had set up a small coal-mine four years earlier, which was destined to develop into a great industry.

The boundary work became more difficult as the men ascended towards the huge, continental backbone; and, for the first time since leaving Turtle Mountain, the axe-men were fully employed. Many bridges had to be built over the various streams; and wide detours were necessary to get the wagons and other equipment through.

Here was presented to many eastern eyes for the first time a magnificent panorama of snow-crowned mountains, timbered valleys, and splashing streams – a new land in every sense, and a hunter’s paradise. Wild life abounded. Luscious trout teemed in the tumbling waters that flowed from the snow-fields among the clouds. An immense herd of elk (wapiti) was seen near Chief Mountain; monstrous moose and small deer were continually in evidence. Mountain sheep and goats stared curiously from their rocky ledges. On more than one occasion, fire-arms were used to provide sport and fresh meat. Grouse were in constant demand. Once, some of the men out ahead encountered a grizzly bear, and preparations were made to lay him low; but, upon the ‘silver tip’ showing fight, the hunt quickly subsided. Later a member of the U.S. Commission shot a mountain lion.

At last the persevering surveyors and their co-workers neared the end of their task at Kootenay River. The line crossed the river at right angles. Pack-horses were used to negotiate the short distance still to go.

About twenty miles remained. But it was twenty miles of hard work; heavy timber that had blown down during wind storms had become interlaced in a bewildering jungle which obstructed the route of travel. In this last span mounds were erected at only two points: the passage of the Belly River and the crossing of Lake Waterton.

The boundary between British Columbia and the United States had already been surveyed from the Pacific coast to the Kootenay when the American Civil War intervened, and a monument had been placed at the eastern extremity. At that time, it had been intended to continue the survey eastward to the Lake of the Woods; but now, a decade later, the actual undertaking had been reversed.

At last the men lay down their tools. It was the end of the trail.

* * *

It was still early autumn, but the weather at night was cold. Many of the men had hoped to winter in the Rockies, and some equipment for that purpose had been transported from Dufferin. Orders, however, were given for the homeward march.

On the return trip, a rest camp was established by the commissioners at Fish Lake in the neighbourhood of Chief Mountain from where the men visited a Missouri trader’s ‘hang-out’ in the vicinity. The least harmful purchases made were cans of brandied peaches. Ponies were also bought from some traders who claimed to be from Fort Whoop-Up on the St. Mary’s River. Inquisitive stragglers from the whisky trading camps appeared on the scene, also a number of U.S. soldiers on a friendly visit from Fort Shaw in Montana.

Another stop was made at the Sweet Grass* Hills. And here on a day in mid-September, the lean and weathered troopers of the North West Mounted Police, under Commissioner French and Assistant Commission Macleod, arrived. With fine camaraderie and jovial spirits, the two forces commingled for a brief spell. Charles Conrad, a prominent trader of Fort Benton, also turned up with a bull-train loaded with oats and other commodities for the police. At that time Fort Benton was a thriving and riotous centre on the Missouri River. It had been named after Col Thomas H. Benton who had played an important part in Washington in fixing the boundary on the 49th parallel. Not least among those present was Jerry Potts, a Piegan half-breed who later became famous as a guide in the service of the N.W.M.P.

Long to be remembered was that stop at the Three Buttes! Thither, in curiosity, had come many Indians, among them a band of Unkapapa Sioux under the noted warrior, Long Dog, a fiery individual who was later to take a major part in the annihilation of Custer’s command on the Little Big Horn, in June 1876, and who afterwards was to become a thorn in the flesh of the Mounted Police when the Sioux took refuge in the Wood Mountain area. In the 7th U.S. Cavalry, accompanying the U.S. commissioner, was Major Marcus Reno who by reason of an order from Custer to attack the Sioux on a separate flank was to be one of the few surviving officers of that historic blood-bath. The city of Reno, Nev., famous for its divorces, perpetuates his name today.

The time passed pleasantly at the Sweet Grass until the inevitable farewells. Some of the men under the U.S. Commission who were released from duty left hurriedly for Fort Benton, which they hoped to reach before freeze-up. From there they could travel eastward towards their homes in mackinaw boats. Navigation by river steamers on the Missouri had already terminated for the seas

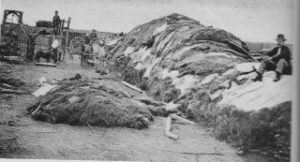

* EDITOR’S NOTE: Sweet Grass was a term commonly used among the plainsmen to designate good pasturage. In this locality it had no reference to the scented grass often used by the Indians in their sacred rituals or in basket weaving. Shortly after their departure, an immense cloud of dust was seen moving in a northerly direction toward the camp. One of the police scouts watched it with an experienced eye, then declared it to indicate a large herd of stampeding buffalo. Onward they came with Indian horsemen hovering on their flanks. Forty mounted men were sent out to turn the animals aside. A concentrated fun-fire split the herd, one division heading north-east, the other north-west. The shaggy beasts intercepted a train which had previously pulled out, and in time they were thundering among the men and horses. One huge bull was shot as its horns became entangled in a wagon wheel. So great was the confusion they created that the surveyors lost twenty-four hours through sheer inability to move on. Few incidents happened on the remaining homeward trek. Once, while passing a large camp of half-breeds, the party paused to watch the women making pemmican – dried and pounded buffalo meat mixed with fat and placed in buffalo-skin sacks. As the returning workmen progressed, they found that prairie fires had swept large tracts of country and thereby deprived of pasturage and the indispensable buffalo chips, they carried wood and forage from one camp to another.

At Frenchman’s Creek they came upon a naked half-breed tied to a tree. He was dead, and obviously had suffered terrible agony. To allow the sun full play, the tree’s branches had been removed, and a near-by stream had added to the man’s torment; for he had been left to die of starvation, thirst and exposure. The on-lookers were stunned at this display of fiendish cruelty by vengeful Indians.

Cameron and his followers experienced trouble with the natives only at Wood End, where one man, who had incurred the enmity of a band, was threatened. Immediately the threat blossomed to include the entire commission. The men formed a corral with carts and wagons, and each was given forty rounds of ammunition. At night skulking Indians were detected, and signal lights appeared on the adjacent hill-tops. Pickets were stationed around the camp, but, naught save a prowling wolf appeared and the expected attack failed to materialize. From then on, however, strict vigilance was maintained; and in due course Dufferin was reached without mishap.

* * *

Part of the N.W.M.P. staff was occupying the buildings at Dufferin, awaiting spring when they would move to the headquarters barracks which were being erected at Swan River, far to the north-west. Later, two troops under Commissioner French, on their return from the Sweet Grass Hills, also spent the winter here, pending completion of the new buildings. Meanwhile, Assistant Commissioner Macleod with three troops had struck towards the foothills and, on reaching the Old Man’s River, erected Fort Macleod – the first police outpost in the Far West. Part of another troop which had accompanied the commissioner eastward, took possession of the uncompleted barracks at Swan River.

The detachment of Royal Engineers, which had formed a large part of the survey party, had left Liverpool on Aug. 20, 1872. The expedition had commenced work at Dufferin on September 30, a month later. And now, after two years, it had traversed more than two thousand miles of desolate region, a land tenanted by tribes who, in freedom from restraint, were second to none in stark and implacable savagery. The expedition had marked nearly nine hundred miles of boundary and accomplished a survey of over five thousand square miles of British territory. During the last year (1874), between May 20 and October 11, a period of 144 days, the two parties had moved back and forth over fifteen hundred miles in longitude, determined and marked 357 miles of the parallel of latitude, and surveyed in detail fifteen hundred square miles.

In addition to all this, they had to contend with many hindrances: the winding of the main trail; the essential wanderings of the surveying parties; the devious routes taken by those distributing supplies; the obstacles of the country itself; inclement weather; heavy transport. Yet the joint expedition accomplished an average of 10 ½ miles a day. Truly a remarkable feat. One that redounds to the credit of the men who executed it. For his services, Captain Cameron received the honour of Commander of Michael and George from her Majesty, the Queen.

Thus, as 1874 drew to a close, an engrossing period of frontier history in North America had begun. And in the making of this land of freedom and opportunity the North West Mounted Police were destined to play an important role.

The 49th was now an established boundary line between two great nations. The lure of the West was on the verge of being a tremendous thing.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: With a single exception, all of the official authentic photographs accompanying this article were generously supplied from the private collection of Mr. W. T. Cameron, son of the late Major General D. R. Cameron who was head of the Canadian Boundary Commission. We wish to express our warmest thanks for these invaluable pictures.

Canadian Indians on the Warpath

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Quarterly October 1941

Canadian Indians on the Warpath.

From away up near the Arctic circle comes proof that the Canadian Indians are doing their bit in Canada’s war effort. In the old days their forefathers used tomahawks; the present-day Indian believes in a stronger weapon – the almighty dollar.

An Indian from the Good Hope in the Mackenzie River area recently handed $10 to the R.C.M.P. for transfer to King George. Another Treaty Indian, Old Jonas of Simpson, N.W.T., dropped into the local R.C.M.P. detachment with $7 which he said was to help the King fight Hitler.

The Indians believe in Britain. Their donations are indications of the loyalty to the Crown that is prevalent among the native population of the Northwest Territories, Canada and Britain will not forget.

How The RCMP Came To Have Black Horses

The Nor’-West Farmer Vol. 49, No. 3 Summer 1984

How The RCMP Came To Have Black Horses

How The RCMP Came To Have Black Horses

By D/Commr. W. H. Kelly (Rtd.)**

During the early days of the Force when horses were the only means of transportation, the NWMP found it difficult to obtain a sufficient number of the right type of horses for the patrol work required of them – long arduous patrols, often with little feed. The “march west” resulted in the death of many horses as well as leaving a large number of them in poor health with a condition known as “alkalied.”

As a result, Assistant Commissioner Macleod, who was in charge of their first post – later to be named Fort Macleod – was forced to send some members into the United States to buy horses, and such trips continued for a number of years. The only horses the Mounties were able to purchase were unbroken bronchos, which in time became just the kind of horses the Force required.

In addition to the horses purchased in the U.S., the NWMP managed to acquire some horses raised by local ranchers to augment the periodic shipments of eastern horses. The latter were never really suited to Force requirements in the west, but because of the general difficulty in obtaining horses it was a number of years before the Force could replace the eastern mounts with horses raised in western Canada or the United States.

Suitability being the determining factor in selection, the NWMP made no attempt to obtain horses of any particular colour. For example, when the Force began its march west to the prairie region from Fort Dufferin in 1874, the mounts obtained from Ontario were so varied in colour that each of the NWMP’s six divisions had a predominantly different hue of horse: “A” Division had dark bays; “B” Division dark brown; “C” Division, bright chestnuts; “D” Division, grays and buckskins; “E” Division, blacks; and “F” Division, light bays. The horses on the march included the forty or so that had been purchased by Acting Commissioner W. Osborne-Smith around Winnipeg in 1873, in preparation for the arrival of the NWMP in the late fall of that year.

When the prairies began to be settled, western businesses and ranchers competed for the type of horse required in the west, so the difficulty in obtaining the right kind of horses for the Force remained. This problem still existed at the time the RNWMP began to mechanize its transportation. Westerners who had used horses began to use mechanical means of getting around. This caused the many horse breeders to go out of business, giving the Force even less choice as to the colour and quality of horses it purchased. Up until the time when black horses were introduced into the Musical Ride, the colour of RCMP horses was generally bay of one shade or another.

It was over sixty years after the inception of the NWMP that the idea of standardizing the colour of its horses came to a man who was in a position to do something about it. In 1935, Assistant Commissioner S. T. Wood had been in London, England, taking a modus operandi course at Scotland Yard, and he was there again as the officer in charge of the RCMP King George VI coronation contingent. On both occasions he saw the scarlet-coated Life Guards on their black horses and was very impressed with their appearance. Some years later,

Commissioner Wood told me that seeing the Life Guards with their black horses had given him the idea that the RCMP should turn to black horses, first for the Musical Ride and then for recruit equitation training.

During this time and for many years thereafter, and as had been done since 1873, the Force purchased its remounts when they were three years old. They were often small in stature, but with proper care and feeding usually grew to the standards required by the Force – 15.2 hands in height and weighing between 1,100 and 1,200 pounds. They were initially roughly broken in and only after an additional four to six months training, when a recruit could safely ride them, were they used for recruit training.

When S. T. Wood became the eighth commissioner of the Force in 1938, word went out to purchase as many black horses as possible. It was soon apparent that a suitable number of horses of this colour could not be obtained, and equally apparent that if the Force was ever to get black horses in sufficient numbers it would have to raise its own. And so it was that, in 1939, a limited breeding program began at the Depot Division stables in Regina.

World War II began that fall and this undoubtedly slowed the implementation of any plans for an extensive breeding program. A few mares were purchased and some of the old equitation mares were transferred to the breeding program. The stallion “King” was purchased at this time. He was black in colour and was the son of an American saddle horse sire and a Thoroughbred/Percheron-cross mare. He clearly showed the Percheron strain.

“King” was not particularly successful as a sire and was replaced by a black Thoroughbred stallion named “Fred Tracey,” rented from his owner in Ottawa at the rate of $35 a foal. However, it soon became clear that the facilities at Regina were not suited to a breeding program commensurate with the

needs of the Force, so consideration was given to moving them elsewhere.

S. T. Wood was familiar with the horse-breeding area of southwestern Saskatchewan. This area included the Cypress Hills and the site of old Fort Walsh, a former headquarters of the NWMP, which later became one of Canada’s official historic sites.

The RCMP purchased 706 acres of land, which included the location of the old fort. Suitable buildings were erected on the exact site of the fort, and a manager (soon to be known as the “wrangler”) was engaged. The Force also leased 2,305 acres of adjacent range land from the provincial government.

There was some delay in acquiring and developing the properties because war duties required all possible manpower and money, and later it was necessary to temporarily abandon equitation training of recruits as well as the colourful Musical Ride. Nevertheless, by the spring of 1943 the property, now referred to in the Force as “the ranch,” was ready to receive the nucleus of the proposed expanded breeding program from Regina: twenty-three mares, eleven foals and the rented stallion “Fred Tracey.”

The problem of obtaining the right kind of stallion was ever present during the early years of the breeding program. Among the stallions used for breeding purposes, one or two were actually chestnut in colour, a colour the Force expected would dominate in the foals thrown by the black mares. During the early period, stallions other than Thoroughbreds were also kept. Later on (with one exception, when “Hymeryk,” a stallion of the Trahkener breed was used), only Thoroughbred stallions were accepted. Although most of these stallions were black in colour, some of them were actually registered as dark brown.

By the 1950’s, black foals began to appear with some regularity, while others were various shades of brown. Occasionally a bright chestnut foal was born, sometimes to a black mare by a black or dark-brown stallion.

The breeding program at Fort Walsh was based on the hard style of raising horses. The animals were kept outdoors summer and winter, fending for themselves on the natural grassy range, with practically no supplementary feeding. The Force horses were rounded up in the fall, identified among others belonging to the neighbouring ranches by the fused MP brand – the Force brand since 1887. The young stock was branded and then put back on the range after the three-year-old remounts had been selected.

Those responsible for the program believed that raising horses in this manner would produce a horse with strong muscles and good bones, and generally tough enough to carry heavy policemen in the saddle. No doubt there was some merit to this view, but some authorities now believe that these good characteristics were offset by the fact that the remounts began saddle work only a few months after leaving the ranch. In the 1950’s, a program of regular supplementary feeding was put into effect, and this not only improved the appearance of the stock but produced better breeding results as well.

Commissioner Wood retired from the RCMP in the spring of 1951, and was immediately appointed a special constable of the Force (without pay) so that he could officially remain involved in the breeding program which he had begun. He spent every summer and fall at the ranch until 1965, when he was stricken with a serious illness which eventually resulted in his death.

By the mid-1950’s the Force was still not producing either the quantity or the quality of remounts that it required, so the purchase of remounts continued mostly in colours other than black. On the advice of several experts, the breeding program was expanded, so as to ensure not only an increase in quantity of foals but in quality as well. The first obvious step was to purchase suitable mares and the price for them was set at about $250 each.

About this same time there was a fear that with the continuous use of Thoroughbred stallions the horses were developing too fine a bone for the work required of them. As an experiment, two purebred Clydesdale mares were obtained from the Dominion Experimental Farm at Indian Head, Saskatchewan, and bred to a black Thoroughbred stallion. No one expected that the result of this mating would produce black saddle horses for Force use, but that the filly foals through subsequent breedings might produce a heavier-boned black horse. The experiment was limited to the extent that only a few filly foals were used in this way, leaving a residue of Clydesdale blood even in some of the beautiful three-quarter or more black Thoroughbred horses the Force uses today.

In spite of the prolonged efforts of the Force to raise its own horses, it wasn’t until the mid-1960’s, 25 years after the breeding program began, that all the horses in the Musical Ride were raised by the Force. Even then, there were a few whose colour was dark brown, not black. Not until the mid 1970’s were all the RCMP horses – breeding stock (except stallions), Musical Ride and equitation – of the Force’s own breeding.

Before this period, however, a great change had taken place in regard to RCMP horses. In the summer of 1966 the federal government, as an economy measure, decided that RCMP recruit equitation training should end, but the RCMP Musical Ride should be retained as a permanent public relations attraction. The government also decided that the Musical Ride operations base should be transferred from Regina, Saskatchewan, to Rockcliffe, Ontario, and that the breeding operation should be moved from Fort Walsh to some place near Ottawa.

The Force realized that if recruits did not take equitation training it would be necessary to retain a number of equitation horses – in addition to those used in the Musical Ride – to train those members in equitation who would volunteer for Musical Ride duty. Thus a number of such horses were also retained, and the remainder were sold in Regina at public auction. At the same time plans were being made to ship the breeding stock to Ontario.

Soon the Force purchased 345 acres of farmland at Pakenham in the pastoral Ottawa Valley, about 30 miles northwest of Ottawa. New buildings and fences were erected and by late 1967 and early 1968, the breeding stock from the ranch found themselves in completely different surroundings. Instead of grazing on the hilly range land at Fort Walsh, they now grazed on the flat prairie-like pastures of Pakenham. Whereas the range at Fort Walsh had never seen a plough, the pastures at Pakenham had been farmland for more than 150 years. Instead of living outdoors all year round, the horses could now be taken indoors during severe weather. In addition, the farm soon began to produce enough hay to feed not only the Pakenham breeding stock, but the Musical Ride and equitation horses at Rockcliffe as well. Despite these differences, there is one great similarity between the ranch at Fort Walsh and the farm at Pakenham: both have fine fresh-water creeks running through their properties.

In the 15 years since the Pakenham remount station was officially opened on December 1, 1968, it has developed into a model horse-breeding station. It was at first under the management of Ralph Baumann, who came to Pakenham from Fort Walsh, and later under the watchful eye of Bruce Parr, Baumann’s assistant at Fort Walsh and later at Pakenham.

The breeding program has not only resulted in the black colour of RCMP horses being stabilized, but to a remarkable degree it has been responsible for their standardization in size, conformation and temperament. These horses must be considered as a definite type of Thoroughbred, even though not of full Thoroughbred blood. However, they cannot be considered as a separate breed, as one international writer on horses had concluded.

The present horses of the RCMP are three-quarters to seven-eights Thoroughbred, with a few pure Thoroughbreds among them, but there is no great concern about these and future horses being too fine-boned for the work they are required to do. Continued attention to the type of stallions and mares used in the breeding program, as well as the continuing practice of not using remounts until they are 5 to 6 years old (by which time they have had about two years training), has resulted in a satisfactory type of horse.

It is now 46 years since the late Commissioner S. T. Wood conceived the idea of the RCMP using black horses, and during that time many of our members have helped to develop the breeding program which today is at peak efficiency. Our beautiful black horses are now seen by more people, at home and abroad, than ever before. As long as the RCMP have such horses they will remain a tribute to Commissioner S. T. Wood. But even he could not have foreseen the high degree of success the breeding program has reached today.

Massacre in the Hills

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Quarterly January 1941

Massacre in the Hills.

Massacre in the Hills.

By John Peter Turner

“Countless deeds of perfidious robbery, of ruthless murder done by white savages out in these Western wilds never find the light of day . . . My God, what a terrible tale could I not tell of these dark deeds done by the white savage against the far nobler red man!”

Food – Festivity – Firewater – Fighting!

Within the scope of these four words may be found the more noticeable indulgences of life along the Western frontier three-quarters of a century ago; indeed all four might avail to signify common usages, past and present, among practically every race of human kind. In varying degrees, man’s tendencies are much the same the world over. Without bodily nourishment life ceases; without diversion, festive or otherwise, it dwindles; “firewater” by any other name has ever been a favourite medium of unpredictable possibilities; and the tendency to shed another’s blood (witness the world today) has thus far proven to be quite impossible of eradication.

Of these pronounced indispensables, so inseparable from early western days, one – the imbibing of intoxicants – has been forbidden absolutely to the Indian; and save to uphold the honour of the nation, the fourth has long since been regarded as an offence at large. But, within the memory of a few still, time was, in one portion of Canada at least, when these four “ways of the flesh”, inflated as they often were to excesses, swayed, as nothing else could, the vagaries of human subsistence and endeavour.

In the early ‘70’s, a barbaric battleground and buffalo pasture occupied the country now embraced by southern Alberta and Saskatchewan and the more northerly parts of Montana. This was the last major portion of the continent remaining to the lndian: a land in which the western intrusion had as yet made small impression, save to introduce, conjointly with the barest benefits, the undermining corrosions of civilization. For the most part, a veritable ocean of perennial grass, veiled from the world by utter solitude, flanked by the Missouri watershed along the south, by the Saskatchewan on the north, by the slowly advancing settlements of Manitoba and Dakota to the east, and by the Rockies on the west, spread immeasurably to the horizons. Along the 49th parallel an international boundary, on the verge of being surveyed, divided the dual sovereignty of this distant land. Rivers, large and small, coursed through its breadth. At its very heart on the Canadian side of the line, the Cypress Hills, accessible by horseflesh from every compass point, rose in broken and irregular configurations above the plain: a weird arena of utter savagery, a neutral tract, tenanted by resident wild creatures – buffalo, elk, moose, deer, grizzly bears, antelope, and other game – and visited by transient stone-age men – Blackfoot, Crees, Assiniboines, Saulteaux and Sioux. Far aloof, at widely separated points, trading establishments flourished, drawing from the wild plains’ hunters an enormous yield in skins and fur. Fort Benton at the head of navigation on the upper Missouri, reeking with tawdry saloons, bawdies, gambling hells and unkempt trading counters commanded an activity that extended northward into Canada. Edmonton on the North Saskatchewan, a staid, well-ordered, almost baronial emporium of the fur trade, stood behind stout palisades at a discretionary distance from the warlike Blackfoot Confederacy towards the south; and Fort Qu-Appelle, to the east, on the margin of the Great Plain, had had its inception as near the vast pastures as safety would permit. Upon these strategic forts encroaching civilization relied in order to tap the resources of the last great Indian wealth; and hither, as well as to a few subsidiary posts, both north and south, red-skinned riders had learned to come spasmodically to barter the products of the hunt and avail themselves of proffered benefits and evils.

At this period, the Montana frontier, the very opposite of the orderly Saskatchewan field of trade, blazed with illicit licence. South of the line, a flagrant disregard for civilized amenities was rampant. The law of the trigger prevailed. White men and red continually vied for mastery. Crime of every description waxed bold and dominant. To be expert on the draw was to boast an enviable superiority. Gold dust was useful, but horses were wealth, power, prestige, and the only quick transport on the plains; and horse-stealing – a deeply-rooted Indian virtue — probably the most unforgivable malfeasance of the West, had become by adoption a popular expedient among a host of hardened freebooters. In glaring contrast to the ethics followed by the Hudson’s Bay Company in the North, trading methods in proximity to the Missouri consisted largely of ghastly inhumanities. For the most part, the decalogue was scoffed at. Calloused persecution of the tribes grew to be a custom – the only good aborigine a dead one. Once stripped of his possessions, the Indian was vermin. Frontier heroes, exponents and expungers of the law, side-armed sheriffs, murderers and degenerates – all the good, bad and indifferent strata of civilized life – constituted a blunt and bloody spearhead that had sunk deeply into the vitals of the West. Benton had grown to be a rough-and-tumble slattern of a place – the congenial rendezvous of reckless adventurers from eastern and southern communities and the haven of gold-seeking backwashes from the western mountains.

Buffalo products furnished the all-important quest; but the big wolves that dogged the shaggy herds provided profitable pelts, as well as ready employment to hard-living profligates and men of shady record. Young squaws were not immune from current prices; the small, wiry horses of the Indian, procurable by fair means or foul, held variable values. Simple commodities were traded to the red men; but liquor held the stage. A tin cup of poisonous firewater would fetch a buffalo roble, sometimes a piebald pony, or a girl with raven braids.

Recognizing no international boundary, the more obdurate Benton traders had instituted a reign of murder and debauchery throughout the Canadian portion of the Blackfoot realm. The establishment, in 1868, of Fort Hamilton (later to bear the more appropriate appellation of Fort Whoop-Up) and the subsequent erection of smaller posts such as Stand-Off, Kipp, Conrad, Slide-Out and High River presaged a state of lawlessness that promised evil to the Canadian scene. By the autumn of 1872, the trade in firewater had spread towards the east with the building of several log trading huts on Battle Creek in the Cypress Hills, chief of which were those of two “squaw-men” Abel Farwell and Moses Solomon. In sheer defiance of the laws of Canada and the United States, brigandage now straddled and controlled the boundary line. Utter ruination of Canada’s Indians of the plains was under way.

And so to our story, gleaned from participants, eye-witnesses, and conflicting records.

The year of 1872 was drawing to its close. The leaves had fallen in the wooded bluffs along the prairie streams. With colder weather threatening, a band of hunting Assiniboines, under Chief Hunkajuka, or “Little Chief,” pondered the selection of a winter camp-site. Far to the north, on the heels of the buffalo masses, the nomadic wayfarers had gathered a goodly supply of pemmican and dried meat. Men, women and children were happy; for in food, above all things, lay the magic gift of life. Not far removed, on the banks of the South Saskatchewan, a camp of Crees – friends and allies of the Assiniboines – were already settled, and thither Hunkajuka decided to repair. There would be festivity aplenty; inter-tribal gatherings of “friendlies” had ever been conducive to sociability. Besides the interests of both camps would be well served, and the long months of cold would pass amid many pleasantries.

During the early winter, there was little to be desired. The dusky tenants of the tapering lodges revelled in sheer contentment. Security and plenty prevailed; festivities, whether rituals or carnivals of food, so dear to pagan hearts, followed one upon another. An occasional buffalo hunt replenished the fresh meat supply and tended to conserve the fast-dwindling pemmican and “jerky.” But soon the latter commodities were all but gone; inherent prodigality had joined with an all-too-free abandon. Worse still, for reasons unknown to the wisest soothsayers, the buffalo herds drew off to other parts. The nightmare of famine, of want beset by winter, loomed as an imminent danger. Desperation fell upon the camp, and quick decisions followed. Little Chief bethought him of the Cypress Hills, hundreds of miles southward, across the whitened plains. It were better to risk the rigours of such a journey than to stay and starve. So, with gloomy forebodings, the Assiniboines bade their compatriots farewell and turned to a bitter task.

Week followed week as the hunger-scourged travellers trudged on. One by one, the aged and decrepit dropped out to die. Ponies and dogs were eaten; and, as these dwindled, the tribulations of the squaws increased. Buffalo skins, par-fleche containers, leather – all articles that offered barest sustenance-were turned to account as food. Wherever old camp-sites were found, discarded bones were dug from the snow, to be crushed and boiled. Hunters ranged desperately to no avail; while, ever closer and closer, the grim spectre of famine trailed the struggling waifs. The cold bit to the marrow. A youthful couple, seeing their only child succumb, decided it was the end; but, so weakened was the crazed young warrior following a self-inflicted knife-thrust in his vitals, he lacked the strength to complete the pact. So his helpmate survived.

The threat of death confronted all! But at last the Cypress Hills was reached; and, camping in a sheltered vale close to Farwell’s post, the exhausted band, having lost some 30 lives, slowly recovered from its recent ordeal. Buffalo were numerous; smaller game abounded about the coulees and brush-clad slopes. Though helpless to travel farther without more ponies, the Assiniboine remnant, released from its bondage of cold and hunger, resumed the normal activity of tribal life. Spring was at hand; buds were now swelling on the aspen trees.

Meanwhile, a related episode was being enacted far beyond the boundary.

South of Farwell’s post, a matter of a hundred miles or more, in Montana, there lies another hilly outcropping – the Bear’s Paw Mountains. Working out from here, a small gang of “wolfers” from Benton had spent the winter trapping and poisoning the tick-coated harpies of the buffalo herds, and doing some trading. April of the historic year of 1873 had come, and the members of the party – all seasoned and unscrupulous frontiersmen – had packed up and were on the move. Mostly, they were men who lived hard, shot hard, and when opportunity offered, drank hard of “Montana Redeye” and “Tarantula Juice”, the principal medium of border trade and barter. With horses loaded, they struck for Benton to “cash in” and indulge in such attractions as they craved. At the Teton River, ten miles from their destination, a last camp was made, and here, while all slept, a band of Canadian Crees, accompanied by some Metis, ran off some 20 of their horses. Arrived at Benton, the maddened dupes, doubtlessly abetted by much liquor, planned a swift revenge. A punitive expedition of about a dozen desperadoes, including the wolfers, well mounted and under the leadership of an erstwhile Montana sheriff, Tom Hardwick, of unsavoury reputation, was forthwith pledged to the recovery or replacement of the stolen stock and to the fullest possible accounting in red-skin blood. At the Teton, the trail of the Cree raiders was picked up and followed, only to be lost some miles to the northward. Nevertheless, resolved to loose their venom upon Indian flesh, the potential murderers pushed on.

While Hardwick and his co-searchers were casting northward, all was not peaceful in and about the diminutive trading posts in the Cypress Hills; nor in the Indian camps nearby. From time immemorial the place had been a general battleground of warring tribes, and more recently the scene of bitter hatreds engendered by the whiskey trade. Horse-stealing and spontaneous killings were confined to neither side. Testimony criss-crosses and is entangled in every attempt to lift the veil from the utter depravity attendant upon the first trading incursions from Benton to this historic spot; records left by one side contradict the other; details are muddled in keeping with the drunken brawls and liquor-crazed homicides staged by whites and Indians. But from sworn statements of whites and the obviously faithful chronicles and memories of several Assiniboines involved – who still live – an account, to all intents and purposes varying slightly from the truth, emerges.

Besides Little Chief’s followers who, devoid of food, had run the long gauntlet of the winter plains, several bands of the same tribe were encamped in and about the hills, – principally one under Chief Minashinayen, who had wintered in one of the many sheltered coulees, and lost a number of ponies to enemy raiders. None of these Indians had been south of the boundary during the winter. With each and every camp the whiskey traders had been driving a brisk and unscrupulous trade for buffalo robes and furs, but, with the first days of spring, the camps began to move to summer haunts. In addition, 13 lodges of wood Mountain Assiniboines had drifted in from the east and joined Little Chief’s camp on Battle Creek, doubtless attracted by the presence of the traders. And some 40 or 50 lodges stood clustered below the shelter of a steep cut-bank, on the east side of the creek, directly across from Farwell’s post.

Ten days previous to the arrival of Little Chief’s band from its painful trek, a story became current that three horses had been stolen from Farwell’s by passing Assiniboines. Perhaps they had strayed, as the corral gate had been left open. In any case, whiskey was flowing freely, and George Hammond, the owner of two of the horses, seemingly an advance member of the Benton gang, had worked himself into a frenzy and sworn vengeance upon all Indians in the neighbourhood. But Little Chief’s Indians, who had consumed or worn out all but five of their own mounts, had picked up one of Hammond’s missing horses on the way in and returned it to its owner.

That same night, in the budding month of May, Tom Hardwick, with part of his gang, rode into Farwell’s. Within the log trading post the lid was off!

Next morning, the rest of Hardwick’s men arrived. Drinking grew boastful. Farwell kept his head, but Moses Solomon joined in the festivities. Meantime, two kegs of liquor found their way, gratuitously, to the Assiniboine camp. Someone at the post, in his cups, turned the horses out from the corral, and, soon afterwards, Hammond announced in whiskey-sodden expletives that his horse, returned to him only the day before, had again been stolen – by the very Assiniboine who had brought it in. Farwell argued otherwise, and offered to have two horses from the Indian camp delivered to the complaining Hammond backing his word by striking out, across the creek, for that purpose. Little Chief readily complied with the request, offering two horses as security. Meanwhile he sent out some young Indians to search for the missing animal, which was found quietly grazing on a nearby slope.

It was now past midday. While Farwell talked to the chief, several of the Benton gang called to the trader to get out of the way. Well fortified in liquor, they were obviously out to kill! Startled, Farwell shouted back that, if they fired, he would fight with the Indians. He urged the gun-men to hold off until he went to the post for his interpreter, Alexis Le Bombard, in order that both sides might talk the matter over. This was agreed to; but barely had he left when shots rang out.

What followed has been the subject of many versions. From intoxicated minds stories would naturally disagree; falsehoods would spring from the guilty; exaggerations from onlookers. The truth would have it that many of the Assiniboines were hopelessly drunk. Thanks to the liquor purposely bestowed upon them, few of the Indians could offer resistance. The chief of the Wood Mountain band, which had recently been added to the camp, lay helpless. Little Chief was in his senses, and the few who were sober, notably the squaws, having sensed imminent trouble, strove frantically to bring the helpless warriors to their wits. The first shots fired may have been from one or more of these – though it would seem that ammunition was woefully meagre in the camp. The 12 men under Hardwick were joined by others including Hammond, their apparent leader, as well as by Moses Solomon, the trader. Two had been left behind to guard the buildings.

No matter the nature of the preliminaries, bloodshed to a certainty was close at hand. Murder, cold-blooded, besotted, and, under the circumstances, particularly merciless and ghastly, was inescapable. Little Chief’s people assuredly had had no part in the horse theft on the Teton. They had committed no greater evil than to drink the white man’s poison. But, in the minds of the Benton gang, it was sufficient for the purpose that they were Indians.

That May-day afternoon was to witness stark tragedy on Battle Creek. Life in the Cypress Hills was functioning true to form; but utter savagery had of a sudden been confronted by a wave of civilization more savage still. Blood-lust, rendered wild-eyed and determined by copious drinking, must needs vent itself – and the Assiniboines had offered the coveted opportunity. On no account would Benton gossip have grounds for ridicule. The robbery on the Teton, even if amends in kind were not achieved, would be well and truly brought to frontier satisfaction by unerring triggers. Indians must pay. Murderous premeditation on the part of Hardwick and Hammond and their satellites has been proven. Had not the gangsters seized a position along a cut-bank commanding the Assiniboine lodges after first speculating upon the lay of the land, the affair that followed might be said to have occurred on the spur of the moment. A galling fire was poured upon men, women and children indiscriminately. Pandemonium reigned among the lodges. To the credit of Little Chief and the few men he could muster for defence, several futile attempts were made to dislodge the murderers by courageously charging the cut-break. But each sortie was repulsed by the unerring storm of bullets hurled upon it.

Their position helpless, with dead and wounded piling up, the Assiniboines raced towards the Whitemud Coulee directly to the east and on the gangster’s left. Here they attempted to make a stand, but Tom Hardwick and one John Evans mounted their horses and outflanked them. They were submitted to deadly fire from the higher ground, and driven to the cover of the brush. Little Chief tried to outflank the flankers, but several men were sent round-about to Hardwick’s support. One of these, Ed. Grace, attempted a short cut and was shot through the heart by an Indian, who bit the dust a moment later. And so the killing proceeded. Hardwick and his supporters drew in from their outpost, killing Indians by picked shots wherever they appeared. The Assiniboines were murdered, routed and scattered to the winds. As the sun sank, the camp was charged, but none save three wounded men, who were promptly dispatched and several terror-stricken squaws, remained. According to the story handed down, the unfortunate women were taken to Farwell’s and Solomon’s posts, there to face a night of drunken bestiality and outrage.